“Here we go, guys,” grins Paddy, our ever-enthusiastic guide. “Another day in paradise!” A firm handshake, a slap on the back, a check of harness and helmet straps later, and we’re back on the move along the notorious Cuillin Ridge.

Our second day high in the Isle of Skye's mountains begins with a short stretch of uphill – typically loose and steep but no more than an exposed walk – before we tiptoe onto the 918m summit of Sgurr a’ Mhadaidh.

It’s a little before 6am and this is the seventh Munro we’ve summited in the last 24 hours, all connected by 6km of shattered volcanic ridgeline. This mountain, though, is the one I’ll never forget.

We’d woken 30 minutes earlier, cocooned inside bivvy bags and surrounded by man-made stone circles designed to protect us from a comatose tumble down the mountainside. The morning had dawned blue and silent, apart from the nearby hiss of a stove followed by the welcome sound of tea being poured.

After a quick brew we’d packed our belongings and made the aforementioned ascent onto the ‘Peak of the Fox’ – which is where you now join us. The sun, which had teased us behind a thin film of cloud the previous day, suddenly blasts us in the face as we crest the ridge, its golden rays massaging warmth into our heat-starved faces.

Below my feet the shadowy length of Loch Coruisk, a concealed loch known as the ‘Cauldron of the Waters’, stretches 2.5km towards the sea. To our left and right are wave after wave of jagged mountains.

We’re standing at the heart of the Black Cuillin – the famed Cuillin Ridge – a chain of over 30 peaks connected by a thin crest of rock that twists and turns across 12km of the most challenging terrain found anywhere in the world.

Formed from the remains of a volcano that erupted then imploded around 60 million years ago, what now stands on the southern edge of Scotland’s second largest island is a huge splintered bowl of spiked peaks, black gabbro cliffs, slender arêtes and hidden carries.

The traverse of this ridge is utterly unique and tremendously dangerous – with over 4,000m of ascent and descent linked by a labyrinth of scrambles, climbs and abseils. So what the hell am I doing here? Allow me to explain…

Day 1

5am: Glenbrittle campsite

My alarm buzzes into life as daylight starts to fill the sky, but I’ve been awake for hours. My tent is pitched at Glenbrittle campsite, with the waves of Loch Brittle licking quietly at the pebbly shoreline just a few feet from my doorway.

This is a day I’ve been building towards with a mixture of excitement and dread for months. I’ve travelled to Skye with three companions, who have all nailed the Cuillin Ridge in both summer and winter conditions, but this is virgin territory for me. I’ve read the guidebooks, studied the maps and watched the YouTube videos, but in terms of ridge experience, I’m pure greenhorn.

I crawl from my tent and peer upwards. The full extent of the challenge isn’t visible from here, but the mountains I can see are formidable. The highest peak of Sgurr Alasdair only reaches 992m, but even from this distance it looks mightily imposing – all turrets, chimneys, gullies, cliffs and scree. We drop the tents, shovel down a couple of bowls of muesli, do one final gear check, then head uphill.

6am: The walk-in

The Cuillin traverse can be done in either direction, but we’re approaching from the south, starting on Gars-bheinn and hopefully finishing 12km and two days later on Sgurr nan Gillean. We begin by ascending gently around the southern mountains until we reach the dramatic entrance to Coir’ a’ Ghrunnda.

Full of giant boulders and huge slanted slabs, climbing upwards into this curved hollow is an early test of my mettle. I stumble a few times, silently cursing myself for being so careless among such experienced companions, who hop effortlessly between the rocks like kids on climbing frames.

“I take it you’re totally comfortable on this sort of ground, Oli?” checks Paddy.

“Yes!” I lie.

“Good,” he replies with a laugh. “Because this is the easy bit.”

He’s not wrong. After a sweaty uphill struggle we reach the spectacular glacial basin of Loch Coir a’ Ghrunnda, as the skies darken to a gun-metal grey. This, I’m told, could be our last chance to fill our water bottles for two days, so we guzzle down as much as we can digest, squeeze as much as we can carry into our packs, then set off in search of the ridge’s start point.

9am: Hitting the ridge

We’re travelling as lightweight as possible, but we go even lighter for the first two peaks. Gars-bheinn (895m) is the traditional starting point of the ‘classic’ Cuillin traverse, but reaching it involves legging it 2km along the ridgeline towards Loch Scavaig, taking in the first Munro (3,000-footer) – Sgurr nan Eag – along the way, then turning around and legging it straight back.

We stash our bags behind rocks before this punishing out-and-back excursion, then half-walk, half-jog and half-scramble across the first two mountains before returning to our rucksacks in an overheated mess. I’m already pretty sure this is my greatest ever day in the mountains, and it’s not even lunchtime.

11am: The TD Gap

If you’ve ever attempted the Cuillin Ridge, or even if you haven’t, you’ve probably heard of the Thearlaich Dubh Gap – more commonly referred to as the TD Gap. It’s the first big challenge you’ll meet from the south and it’s arguably the most difficult obstacle on the entire ridge.

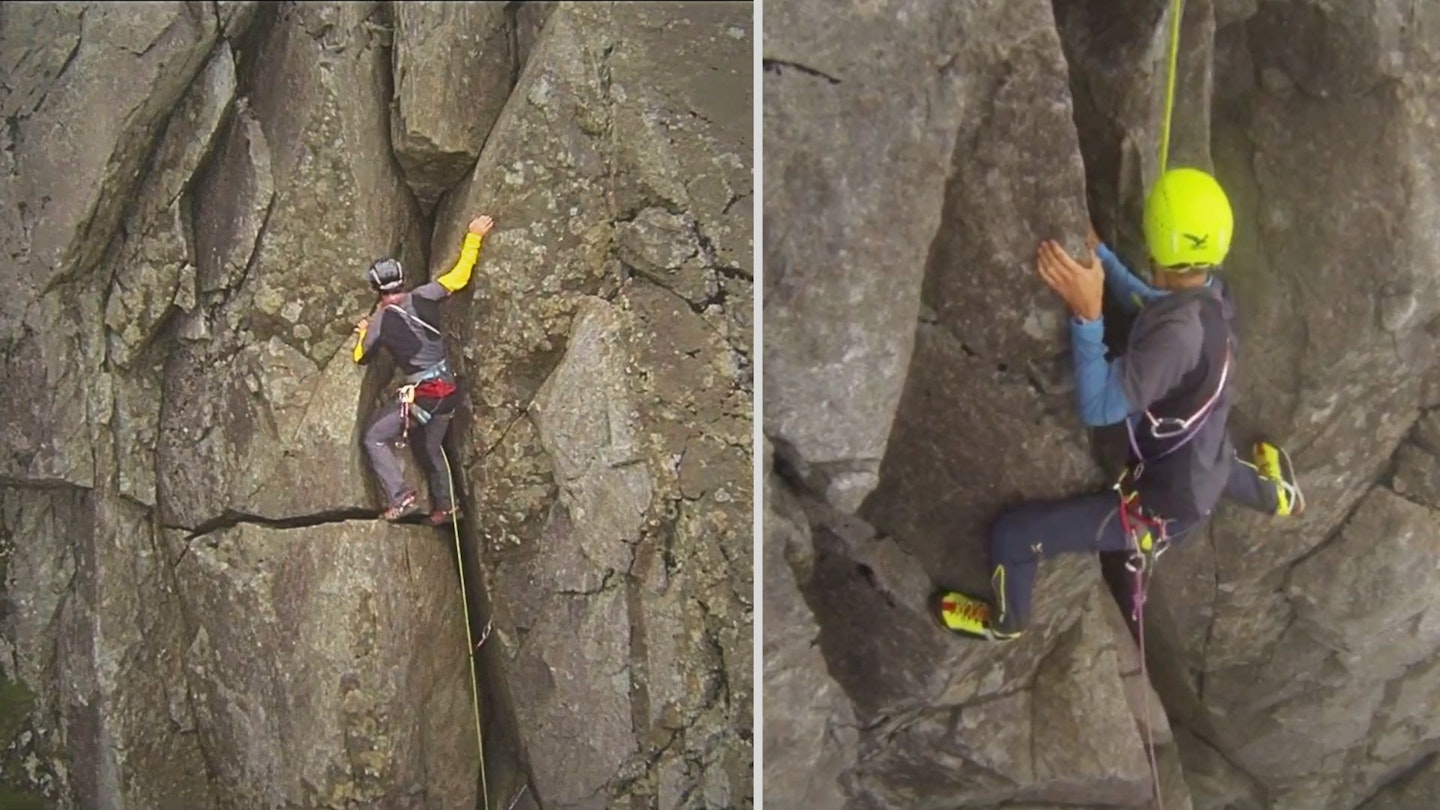

As we arrive at the Gap – a greasy, 30ft deep slash in the mountainside – I realise I’m not going to enjoy the next half an hour. There’s drizzle in the air, the grey walls look far more intimidating than they did in the photos, and suddenly I’m trusting my weight to a thin sliver of yellow rope and rappelling into the abyss.

I feel sick with nerves as I perch on the wonky boulder that’s fallen from some ungodly height above before wedging itself in the throat of the Gap, with don’t-look-down drops tumbling away on both sides. I watch anxiously as far better climbers than me huff and puff their way out of the Gap, and then, horrifyingly, it’s my turn.

“Suddenly I’m trusting my weight to a thin sliver of yellow rope and rappelling into the abyss.”

The rope goes tight around my waist, and straight away I know I’m out of my depth. But I also realise something – if I can get through this then I can probably get through anything the Cuillin Ridge throws at me. So I keep going – grabbing at edges with my fingers, wedging knees and elbows into cracks, heaving myself upwards with arms and legs until somehow, unbelievably, I’m out.

1pm: Sgurr Alasdair

Time starts to pass in a blur. We climb quickly to the top of Sgurr Alasdair, our second Munro and the highest point of the Cuillin Ridge. Paddy keeps me on a short rope for security, but we’re moving together freely rather than anchored to a fixed point.

It’s a fast and effective way to travel, and although it means our concentration must remain razor-sharp (because if I fall, his body weight and quick thinking are the only things saving us both from a long drop onto hard rock), we start eating up distance quickly.

We clamber over Sgurr Thearlaich, tottering along narrow strips of rock the whole way, then tackle two more abseils before squaring up to Munro number three – Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, named after famous Skye guide John MacKenzie.

The climb up King’s Chimney to Mhic Choinnich’s summit is longer and more exposed than the TD Gap struggle, but it’s far more enjoyable. I wriggle to the top, take a deep breath, then ask what’s next… “The In Pinn!” comes the reply. “If you like what we just did, you’re going to love this.”

2pm: The Inaccessible Pinnacle

The ‘In Pinn’ has possibly the coolest name of any UK mountain, and it’s also the toughest obstacle for anyone trying to ‘compleat’ the Munros.

It's essentially a terrifyingly huge dagger of rock jutting from the summit of 978m Sgurr Dearg, and it has been granted Munro status as it reaches eight metres higher than the mountain it occupies. For mere mortals the In Pinn can’t be climbed without the use of a rope, or descended without the aid of an abseil, and the sight of it is enough to set your stomach spinning.

The regular way up is via the east ridge, which in many sections is no wider than a 30cm ruler, hence its Moderate rock-climb grade. The moves are simple, but the exposure is sensational: to either side is nothing but fresh air, with drops of up to 600m plummeting from its northern edge.

The good news, though, is that the moves are bordering on easy, the rock is grippy and the holds are gigantic. I fly up the early sections and just as I start to enjoy myself, I’m lowering myself back to Earth and heading in search of the next challenge.

4pm: Exhaustion

We’re somewhere between Sgurr na Banachdich and Sgurr a’ Ghreadaidh (Munros five and six of the day) when the scale of the challenge catches up with me, then completely overwhelms me. The constant movement, constant exposure and constant amount of mental effort required have drained almost every remaining reserve of energy I possess.

Everything – every tower, arête and scree chute – has started to look the same. I know I’m crossing buzz-saw ridgelines, toothy summits and tackling Grade 3 scrambles, but I also know that tomorrow I won’t remember any of them. I need a hot meal, I need sleep, and I need them fast.

7pm: Bivvy spot

We reach the gap of An Dorus, a notch in the ridge that offers an escape route to the west if you’ve decided enough is enough, but we’re not going anywhere. This is, however, as far as we’re going today.

I shovel down a hot meal (couldn’t tell you what it was but I remember it tasting magnificent), crawl into my sleeping bag, snap some photos as the last traces of daylight blend into the horizon over the Hebrides, then drift into unconsciousness.

Day 2

6am: Early-morning exposure

If I’ve ever been more nervous than this, I don’t remember it. After the initial euphoria of basking in golden sunshine atop Sgurr a’ Mhadaidh (Munro seven), the realisation of how big a challenge remains starts to sink in.

We’re halfway along the ridge and the weather forecast is perfect, but the route ahead looks horrifying. This section appears even thinner, even more exposed and even more unstable than anything we’ve encountered.

We begin by descending polished slabs that slope perilously away from us, along a thread of rock with nothing to the right of it. The consequences of taking a careless footstep on what feels like a shabbily constructed seesaw aren’t worth thinking about.

Another rock-climb follows, accompanied by the usual overdose of exposed scrambling, and then the peaks start flying by.

The trident-shaped outline of Bidein Druim nan Ramh is a nightmare to ascend and needs two abseils to descend, then An Caisteal stretches my nerves to breaking point as we leap over the wide ‘crevasses’ that puncture its flanks.

It feels like impossibly hard work as we ascend Bruach na Frithe (Munro eight), with my brain as fried as my legs and arms, but we’re inching ever closer to the finish.

12pm: The Bhasteir Tooth

I’ve done many daft things in my life, but none compare with Naismith’s Route on the Bhasteir Tooth. When someone suggests you should climb an enormous rock fang hanging off a mountain whose name translates as ‘The Executioner’, you should realise something unbelievably distressing is about to happen – but nothing could prepare me for this.

I watch Paddy swing out onto a narrow ledge, then vanish up a vertical wall I can’t see the top of. ‘Surely that’s not what I’m climbing,’ I think as I stand quivering below. I’m alone with my thoughts for 10 minutes as Paddy secures ropes somewhere high above, then instructs me to climb. I’m frozen with fear.

All that’s visible above is a 35m wall splintered by thin cracks and I’m not sure which route Paddy took. I follow the rope, edging first along, then upwards. My mouth is dry, but my hands are soaked in sweat. Bad combination. I’m climbing with desperation and adrenaline rather than skill and poise, and I’d rather be anywhere else in the world than here.

I inch upwards, step by step, hand over hand, until eventually Paddy’s face comes into view. He’s grinning, mostly out of pity, as I collapse on a rock shelf next to him. “Congratulations!” he shouts. “That’s the last of the big challenges!” I’m so happy I feel like crying.

3pm: End in sight

The challenges aren’t totally over, of course. We still have to summit the rock fortress of Am Basteir (934m, Munro number nine) before taking a direct line up Sgurr nan Gillean’s west ridge.

Shaped like a witch’s hat and with a clutch of spindly pinnacles to slalom through en route to the summit, it provides a grandstand finish. Before long I’m sitting on top of our final mountain, staring back along the hooked expanse of the ridge, and I can’t believe what we’ve achieved.

The route is so long and complicated it’s hard to decipher what we’ve climbed and what we haven’t, or even where we started. I shuffle off ‘The Peak of the Young Men’ feeling 100 years old, sleepwalk through the final abseil, unclip my harness and helmet, then stumble towards the bar at the Sligachan Hotel.

Cuillin Ridge Traverse – FAQs

How hard is the Cuillin Ridge?

How scary was it? Did I relax enough to enjoy myself? Would I do it again? Those are the three main questions I've been asked since I returned from Skye. Quite simply, it was the toughest thing I’ve ever done. It knackered me physically, but it was the mental exhaustion that shocked me.

Unless you’re incredibly relaxed with heights, being exposed to that level of danger for such sustained periods will drain you like it did me. I left the ridge with my fingertips scorched, dripping in sweat, gasping for water and with my brain scrambled; but they were the two most exciting, enjoyable and rewarding days of my life.

Would I do it again? No chance: I got away with it once, and that’s more than enough for me.

What's the best route?

The route across the Cuillin Ridge described in this article followed what is traditionally regarded as the ‘classic traverse’ from south to north, starting on Gars-bheinn and finishing on Sgurr nan Gillean.

This route misses out the 944m Munro of Sgurr Dubh Mor, which lies slightly away from the main spine of the ridge between Sgurr nan Eag and Sgurr Alasdair. Sgurr Dubh Mor is, however, often included by peak-baggers who want to summit all 11 Munros in the Black Cuillin as part of their traverse.

Here are the peaks we summited in the order we climbed them:

Gars-bheinn, 895m

Sgurr nan Eag, 924m

Sgurr Alasdair, 992m

Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, 948m

Inaccessible Pinnacle, 986m

Sgurr na Banachdich, 965m

Sgurr a' Ghreadaidh, 973m

Sgurr a' Mhadaidh, 918m

Bidein Druim nan Ramh, 869m

Bruach na Frithe, 958m

Am Basteir, 934m

Sgurr nan Gillean, 964m

How technical is a full ridge traverse?

The Cuillin Ridge requires the full range of techniques, from mountain walking on rough terrain to scrambling and pitched rock climbing. To succeed, the speed/safety equation needs to be balanced. Soloing is obviously fast but allows no margin for error.

Pitching climbs is potentially very safe but also time-consuming, so a balance needs to be struck whereby you are fast enough to finish the ridge but within acceptable (to you) safety margins. For a team to succeed, it needs to solo the vast majority of the ridge, but most teams will use ropes for the climbs and abseils.

How fit do I need to be for the Cuillin Ridge?

The ridge has 12km of scrambling, 4,000m+ of ascent/descent, several classic climbs and some abseils to say nothing of the three-hour walk in and the same out. A high level of fitness is therefore a prerequisite. Alone, it won’t guarantee success but it will improve your odds and enable you to make the most of any weather window.

Most teams will not only be physically exhausted by (or long before) the end of the ridge but also mentally drained. Don’t make the mistake of underestimating the mental pressure of constant scrambling in potentially dangerous situations for hour upon hour, especially as the time ticks by and darkness draws ever closer.

What preparation will I need?

Your preparation should involve long days that include rough walking and scrambles, or enchainments of easy climbs wearing a fully loaded pack and your choice of footwear.

Practise, for example, in Eryri (Snowdonia), on Idwal Slabs then Cneifion Arête before carrying on along the tops to do something on Tryfan. For the full pre-Cuillin dry run, you could then carry on to do the Snowdon Horseshoe or the Amphitheatre Buttress.

If you're planning to do a multi-day ridge, then get out and practise with full bivvy gear so that everything becomes second nature to you.

If time allows, try to get to Skye and get on some of the classic scrambles before your ridge traverse. Practise leading with a fairly minimal rack so that you get used to placing less gear and running things out a bit more than usual.

How long does the traverse take – one day or two?

Light and fast, or heavier packs but the amazing experience of a night high in the mountains – which would you prefer? If you are just there to tick the ridge and have the necessary ability and fitness, then a one-day traverse is a good option. Others will relish the longer time spent in the mountains.

How hard is navigation on the ridge?

Should you be lucky and have great weather with wall-to-wall visibility, you may well wonder what all the fuss is about. More likely, visibility will be less than ideal. In theory, a ridge sounds easy to follow but in practice it is hard to envisage a more complex navigation scenario.

Abseil slings left on spikes, signs of wear ending in an impassable cliff, and dead-end paths can all be indications of navigational errors made by previous teams. Conversely, signs of wear, abseil slings and so on, can and do mark the correct route, so you need to be selective and use common sense.

The Cuillin is also notorious for its magnetic rocks and, as such, compasses cannot be wholly relied upon. You should definitely not just rely on a GPS unit as your sole means of navigation. Hiring an experienced guide is obviously a great option!

How do I get to the start of the ridge?

Unless you have access to two cars, you may need to use public transport or hitch to retrieve parked cars, especially if accessing the ridge from Elgol.

Buses aren't that frequent and many are linked to ferrying school children. There are no buses to Glen Brittle, but there is one to Elgol from Broadford. Plan accordingly using the Traveline website.

Taxis are expensive and can entail a long wait. Remember mobile reception is non-existent in many places (Glen Brittle for example) and poor elsewhere. It's good on much of the ridge, so if you're sure of a time then you could risk phoning ahead and trusting to luck. Boat trips from Elgol to the landing steps by the hut at Coruisk are £20 each way and are run by Misty Isle Boat Trips.

What gear do I need for the Cuillin Ridge?

Travelling light is vital on Skye, as you’ll be tackling technical terrain and moving constantly. Here’s some of the vital gear you’ll need.

Backpack: A 40-litre pack should be large enough to carry your climbing and bivvy gear, plus warm layers and food. It must be robust enough to survive bashing against rocks.

Durable boots: The coarse gabbro rock makes mincemeat of flimsy walking boots. Shelling out on dedicated scrambling boots will pay dividends.

Quality socks: You'll be on your feet for two days solid, so the last thing you want is blisters.

Cooking gear: Keep your stoves, mugs and bowls light, but make sure they’re reliable.

Water bottle: You should carry at least two litres of water in your pack, probably more, as it can be scarce up high.

Harness: You’ll wear this most of the day, even on the walking sections, so make sure it's comfortable and fits well.

Helmet: Because your head contains a very important organ!

Bivvy, sleeping bag, mat: Take a bivvy bag rather than a tent, a lightweight sleeping bag and a ¾-length sleeping mat to cut weight.

Food: Camping ready meals are the quickest options, whereas things like couscous are very light. Pack plenty of snacks to eat on the move, because you’ll burn lots of energy.

Head torch: You’ll need this when you bivvy, and there’s a chance you could still be traversing after dark.

Warm layers: You’ll be warm while you’re moving but you’ll spend lots of time standing still while belaying or setting up climbs, so you could get cold quickly. Pack insulating extra layers, plus hat and gloves.

Waterproofs: Haven’t you heard? It rains a lot in Scotland. Bring both a good waterproof jacket and waterproof trousers.

Mobile phone: Can be used for anything from emergency calls and photos to GPS fixes and weather updates.

First aid kit: You’re a long way from anywhere for most of the traverse, so a well-stocked first aid kit and the knowledge to use it are vital.

Midge repellent: Trust us, you're going to need it.

Watch the video of our Cuillin Ridge traverse

About the author

Our editor Oli Reed (above) has walked, camped, scrambled and climbed on Skye many times and classes this two-day traverse of the Cuillin Ridge as his greatest achievement in the mountains. He's been back to the island numerous times since and his main piece of advice is to make sure you're prepared.

There's nowhere quite like Skye, with mountains so inhospitable they feel like they're trying to throw you off with every footstep. If you don't fancy the full ridge traverse yet, check out the great single-day routes on Sgurr Alasdair and Sgurr nan Gillean that give you a real flavour for what Skye's all about.