One thing you can guarantee if you’re hillwalking in the UK is that you’ll get a proper soaking at some point. So reliable waterproof hiking jackets don’t just keep you dry, they offer vital protection in the full range of unpredictable conditions in all seasons.

A reliable waterproof jacket is high on the list of walkers' gear purchases. But with so many options and features available it can be a bewildering buying experience.

This guide to waterproof hiking apparel will help you find the perfect jacket and waterproof trousers for you, and will ensure that your money is spent on the right product for your needs.

Know your gear jargon

Let's begin with explaining three key parts of waterproof fabrics: waterproof ratings, breathability ratings, and fabric type.

Waterproof ratings

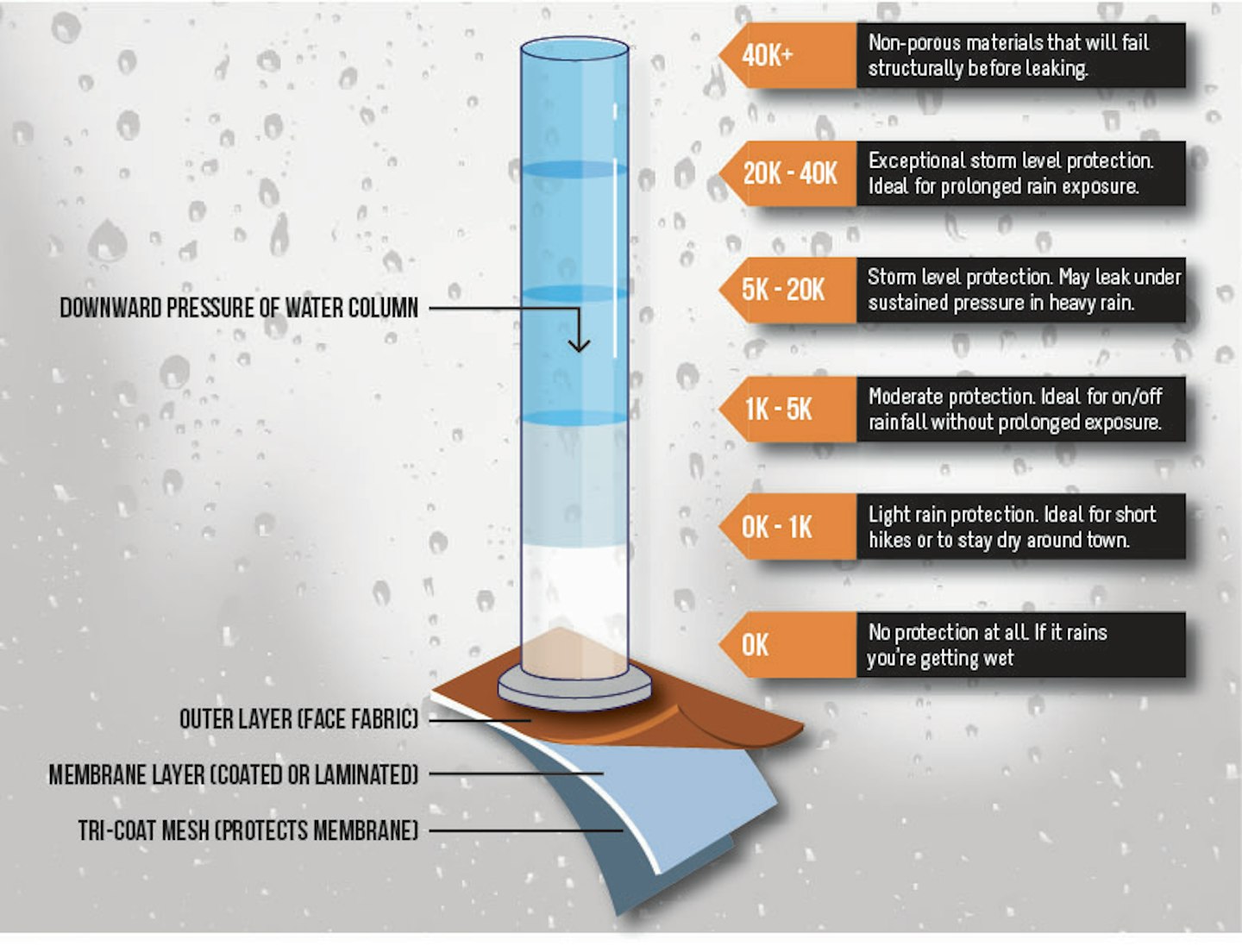

The term 'waterproof' sounds absolute but there's a scale of fabrics' ability to block water ingress. A waterproof fabric's 'waterproofness' is quantified by something called hydrostatic head (HH for short).

Hydrostatic head ratings are measured in millimetres. For example, you might see a jacket with a waterproof rating of 15,000mm HH. This means the fabric can withstand the equivalent pressure of a 15-metre column of water before water begins to soak through.

Manufacturers use a machine to mimic this water pressure and it sounds like an odd means of testing at first. But waterproof gear often has to block rain while experiencing extra pressure applied by backpack straps for example. The same goes for waterproof fabrics used for tents.

<3,000mm HH: Water repellent

3,000-5,000mm HH: Water resistant

5,000-10,000mm HH: Waterproof with light resistance

10,000-15,000mm HH: Waterproof with good resistance

15,000-20,0000mm HH: Waterproof with high resistance

>20,000mm HH: Waterproof with highest resistance

Breathability ratings

In addition to waterproof ratings, a waterproof fabric's breathability is important too. A fabric's breathability is how well it allows moisture to escape. Hiking fabrics need to be breathable because condensation build-up inside your clothing acts as a thermal conductor and sucks away your body heat. This is uncomfortable and in extreme cases can be a contributing factor to hypothermia.

Using jackets as an example, those used in warmer climates or in circumstances that require high levels of energy excursion need to be more breathable than those intended for everyday use of leisurely hillwalking.

A common means of measuring a waterproof fabric's breathability is Moisture Vapour Transmission Rate (MVTR). The unit of measurement for MVTR is grams per square metre per day (g/m²/24hrs). It sounds complex but works in a similar way to hydrostatic head ratings. The higher the value, the more breathable the fabric is.

A low MVTR rating (e.g. 8,000g/m²/24hrs) means the garment is less breathable; higher ratings (e.g. 40,0000g/m²/24hrs) indicates the garment is more breathable.

Resistance to Evaporative Heat Transfer (RET) is another measurement for establishing a fabric's breathability. In contrast to MVTR, the lower the RET rating, the more breathable the fabric is. But these ratings shouldn't be taken as gospel because there are various means of testing it. So use it as an indicator only.

Just before we move on, to maintain a garment's waterproofness and breathability it needs to be cleaned and cared for properly. This is easy to do, but must be stressed that particular cleaning products should be used, which we recommend in our guide to waterproof clothing and tent care guides.

2-layer, 2.5-layer, and 3-layer explained

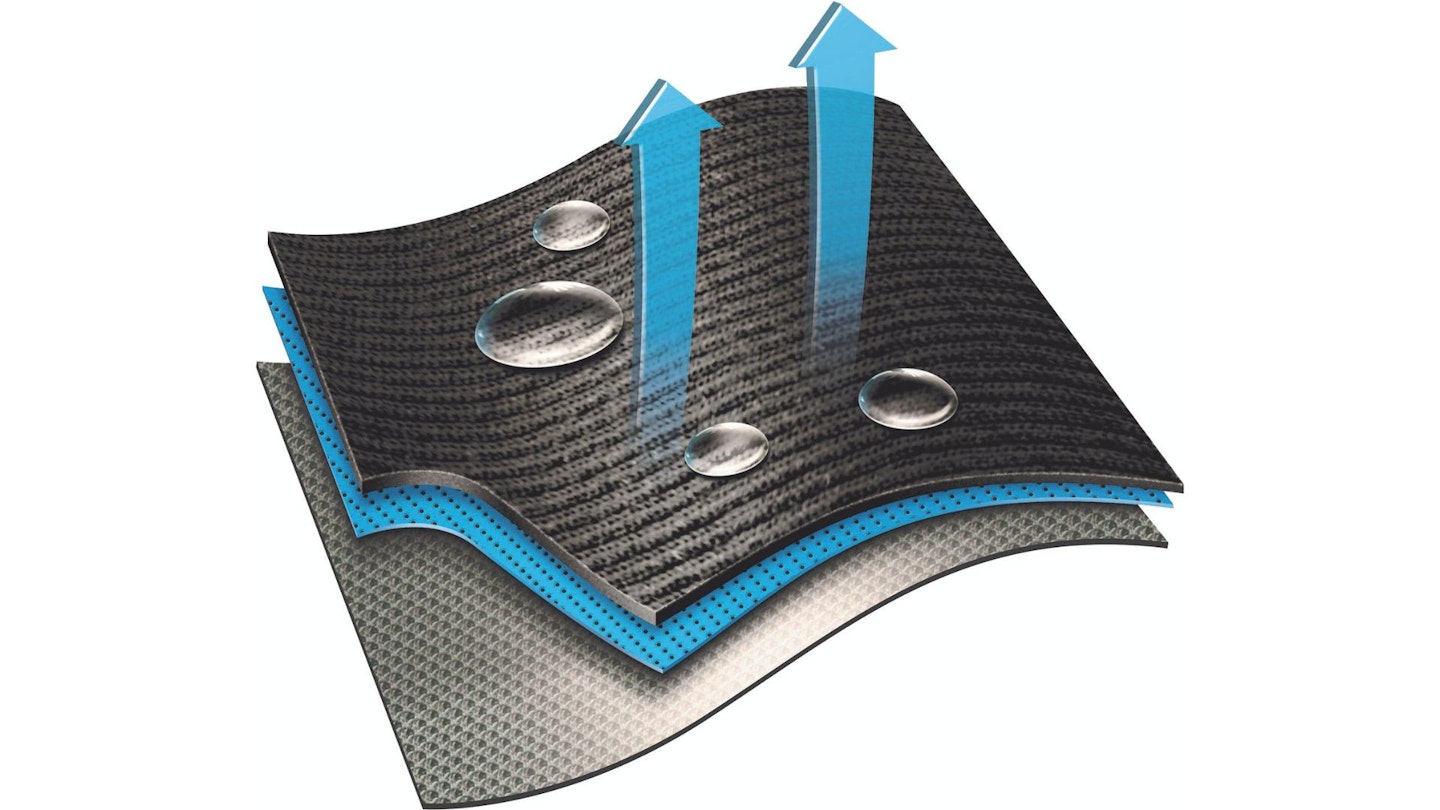

Waterproof garments have layers. These consist of an outer or 'face fabric', membrane, and inner layer. The different type of inner layer determines whether a fabric is 2, 2.5, or 3 layer.

The outer/face fabric is bonded to the membrane. It is usually made from polyester or nylon and it protects the membrane from abrasion and dirt, and aids water repellency by providing a surface on which to apply a DWR.

A backer is used on the inner surface of waterproof-breathable fabrics to protect the membrane and provide extra comfort. A 2-layer jacket has no backer, instead employing a separate mesh or taffeta drop liner. A 2.5-layer jacket uses a raised print or pattern (considered a ‘half-layer’, hence 2.5), while a 3-layer jacket uses a full bonded textured or mesh layer that creates a sort of sandwich, with the membrane in the middle and the face fabric on the outside.

There are reasons for having three types. Three-layer jackets make for the most durable and effective shells but are also the most expensive; 2.5-layer jackets are cheaper, lighter and more packable, but can sometimes feel a little clammy; and 2-layer jackets are comfortable to wear, but the need for a separate liner makes them bulkier and heavier.

DWR

This acronym stands for Durable Water Repellent treatment, and this finish is largely what causes rain to bead and roll off your jacket. It’s an essential part of modern waterproofs, because if the face fabric becomes saturated (a process called ‘wetting out’) the membrane cannot breathe effectively, leading to moisture build-up inside your jacket.

Unfortunately, most Durable Water Repellent treatments are not actually very durable – in fact, they can degrade quite quickly. This is why regularly cleaning and reproofing your waterproofs with specialist products is so important.

What will you use your jacket for?

If you’ve stared at the endless options for waterproof trousers and particularly jackets, you’ll know there are loads of different styles depending on the kind of adventure you’re planning.

You get specific hillwalking options, lightweight summer shells, heavy-duty winter jackets, and high-spec designs built for high mountains and alpine terrain. The key is to find one or two that will work across all of your mountain trips.

Begin by making a list of the priorities you need (high waterproof rating, durable, lightweight, under £200, etc) and whittle down your options from there. Take your time, it pays to be fussy.

Find adjustable features

One of the best features of a good waterproof jacket is adjustability. Key areas you’ll want to be able to adjust so they fit your body shape better are the hood, hem and cuffs. This is usually done through a variety of drawstrings, toggles and Velcro tabs.

The key things with hoods are movement and visibility. Once you’ve adjusted and tightened them up to offer as much protection as possible, remember you still need to be able to rotate your head to see where you’re going.

Ventilation

Waterproof fabrics are getting more breathable every year, but some jackets offer more ventilation options than others. Adjustment in the cuffs helps, as it lets you roll your sleeves up, while pit zips allow you to open up the whole area underneath your arms.

Find the fit that works for you

Waterproof jackets come in all shapes and sizes – long ones, short ones, loose ones, tight ones. Some people like the jacket to fall way below their waist, while others prefer it to sit on the hips. If the cut of the jacket is loose, it allows more layers underneath. Meanwhile a more athletic fit will feel snugger around your torso. Try a few styles on and go for the one that moves best with your body shape and walking style.

Check out the zips

Zips and hoods can make or break a waterproof jacket. Despite big recent advances in technology, zips are still a weak point for water repellency, and water often finds its way through zips. So, stormflaps that cover the area over the top and beneath the zip offer extra protection.

When you try on a waterproof jacket in the shop you probably won’t have your rucksack with you, so grab one off the shelf and buckle it up. What you’ll often realise is that the pockets can get obstructed by rucksack straps, meaning you have to take off your whole pack to access what’s in them. A good selection of chest pockets and high-sitting hand pockets is usually best. These allow you to easily access key bits of kit, like gloves, snacks and maps, as you walk.

Waterproof trousers

Most walking trousers don’t come with a waterproof lining, so another key addition to your hillwalking wardrobe is a good pair of waterproof overtrousers. Look for a pair with zips that fully open from hip to ankle, so you can put them on without taking your boots off.

Sustainability

These days, waterproof fabrics used for making jackets, trousers, and tents almost always use synthetic materials. Nylon and polyester aren't the most environmentally friendly materials but there are some things you can do to ensure your garment or piece of equipment is as sustainable as possible.

Look for the use of recycled materials and a fluorocarbon-free (PFC-free) Durable Water Repellent (DWR) coating. Gore-Tex has introduced a membrane, which lives up to their 'Guaranteed To Keep You Dry' promise, while lowering its footprint.

Can waterproof jackets lose their waterproofing?

Shiny marketing bills some waterproof fabrics as infallible, if not miraculous, pledging they're “guaranteed never to leak” and “100% waterproof”, or something to that effect. But these pledges have caveats, and it’s important to learn the limitations of your kit.

Yes, in an ideal world we would all prefer the waterproofing to work every time, without fail. But a touch of realism suggests we need to put in a bit of effort, care and time to get the best out of our kit.

Waterproof clothing can stop being effective for a number of reasons. One is that the membrane’s waterproofing and breathability has become compromised through the buildup of dirt, sweat, food, sun cream, oils from your skin, and all manner of other foreign particles. The simple solution to this is to give your garment a proper clean, which is easy and can be done yourself at home.

Another is that the garment’s durable water repellent (DWR) coating has (or has started to) wear off. This is most common around areas of a garment subject to more wear and pressure, such as a jacket’s shoulders where backpack straps sit.

Garments get a DWR treatment applied to increase their ability to shed water. DWR treatments aren’t permanent (although some innovations are starting to challenge this), and require reapplication. Just like cleaning, reproofing is easy to do yourself at home too.

Our guide to cleaning waterproof fabrics explains how to clean and reproof your gear, and which products to use.