Conventional wisdom has it that when it comes to outdoor clothing – much like in croissant production – several thinner layers are better than a single, thick one.

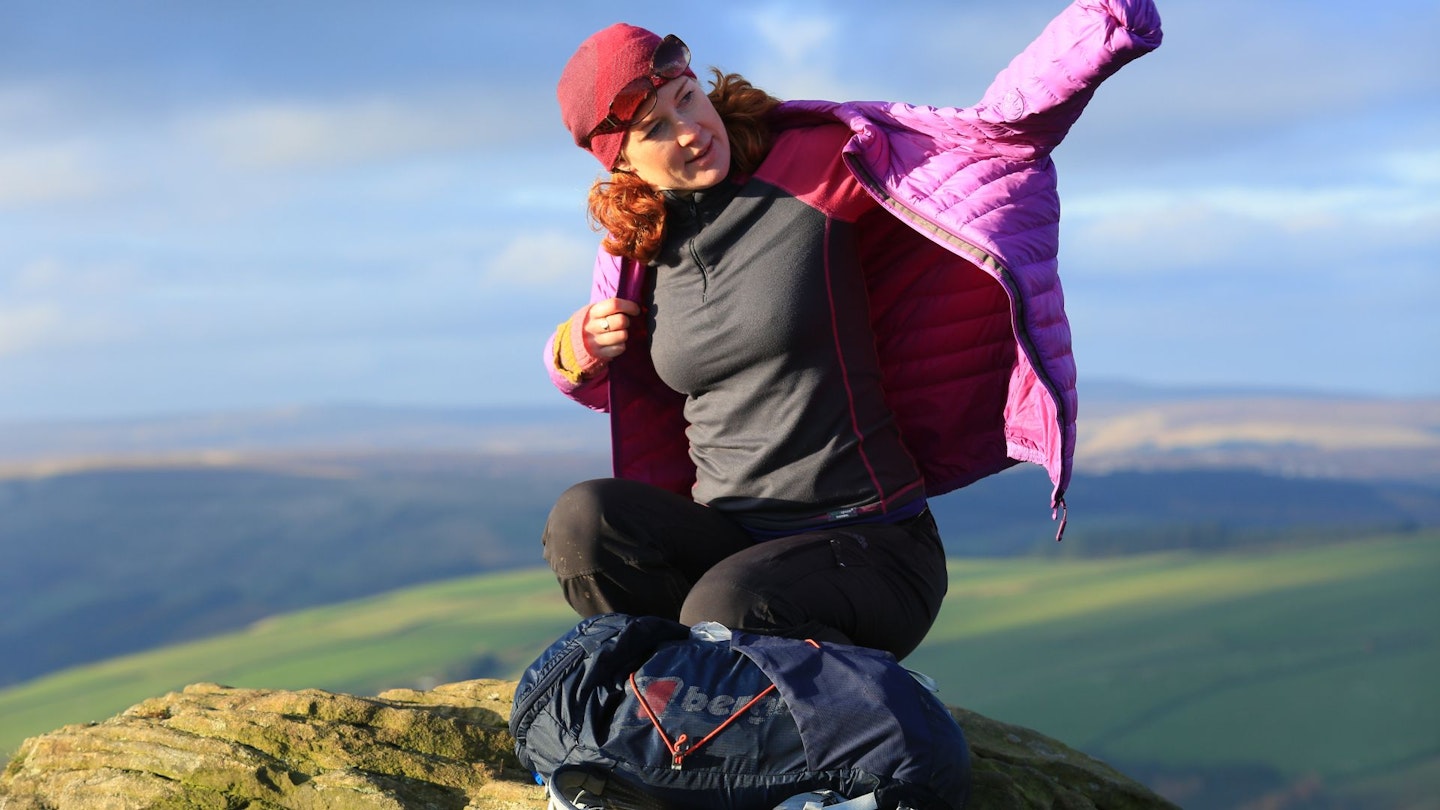

Having several layers enables you to better adapt to changing circumstances and conditions. Layers can be removed or added: if it gets cold, pull on a fleece or down jacket; if it starts chucking it down, grab your Gore-Tex waterproofs; or if the ascent steepens dramatically, strip off to your base layers. (If you're climbing it, of course - you don't just want to be there looking at a hill in your long-johns.)

With only one or two items of clothing in your arsenal (say, a thick hoodie and an insulated parka), you simply can’t adapt to the mountains in this way – and you’re far more likely to end up too hot, too cold, wet from rain, excessively sweaty, or unprotected against the wind. The real beauty of the layering system is that you can fine-tune your clothing with constant minor adjustments to suit your body.

How to layer clothes for hiking

There are many versions of the layering system, depending on personal preference, season, conditions and exertion levels. But a common approach is a simple, 3-layer system consisting of a base layer, mid layer and outer layer. The base layer is for moisture management and sweat wicking; the insulating mid layer is for warmth; and the outer layer is to keep the wind and rain at bay. Each layer has a very different function, but together they should work in harmony as part of a versatile and efficient overall system.

Does it all work? In practice, the 3-layer system is well-tested and performs capably. But it certainly isn’t faultless. The biggest challenge is moisture management. Ideally moisture vapour will pass through all the layers including the outer shell, ensuring you stay dry on the inside – but even the most breathable of waterproof jackets can cause condensation and leave you feeling clammy.

Similarly, it’s easy to misjudge your mid layer needs. You might end up too warm or too cool, plus if your mid layer isn’t water-resistant or windproof you’ll constantly be forced to wear an outer layer even in just light showers or chilly breezes. Yet, despite these flaws, the layering system is still the best approach to clothing for hillwalkers.

The layering system in detail

Base layers

Base layers are worn directly against the skin, with a snug (but not restrictive) fit. Their role is to regulate body temperature and wick moisture away from your skin. Too often hillwalkers neglect the humble base layer in favour of splashing the cash on jazzy insulated jackets and waterproofs, but this is a flawed approach – if your cotton t-shirt is damp with sweat and failing to dry quickly, you’ll end up cold and uncomfortable even if you are wearing a £400, top-of-the-range down jacket.

Instead you should always wear a lightweight, technical and fast-wicking base layer as your foundation layer. But merino wool or synthetic polyester? That is your biggest decision in terms of fabrics. Merino wool base layers are warmer than synthetic ones. They are also odour-resistant, fast-wicking and more comfortable when wet, but generally more expensive.

Synthetic base layers are better value, with faster wicking and drying, but inferior warmth. A popular strategy is to opt for merino wool base layers in colder climes and synthetic layers for milder conditions or during higher-intensity activities.

Base layers are often season-specific too. Heavier, thicker and higher grades of merino wool (measured in gsm – grams per square metre) will provide more insulation for winter, while some ultra-light synthetic base layers are designed to keep you cool and dry in summer. Hybrid base layers blend merino wool and synthetic fibres into one product with the aim of retaining the best properties of both.

Perhaps the most commonly used base layers are short-sleeve t-shirts for hiking, and long-sleeved thermal tops and long johns for camping, but don’t forget about technical underwear. Technical products, such as merino boxers, bras and pants, will perform far better than your everyday pairs.

Recommended hiking base layers:

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

Icebreaker's proven 200 Oasis base layer provides the warmth, breathability and next-to-skin comfort needed for an array of mountain sports.

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

Offering lightweight warmth and moisture-wicking performance, the Capilene's double-knit fabric also has a HeiQ Fresh treatment for lasting odour control. Comfortable and durable, raglan sleeves and underarm gussets aid mobility while thumb loops help keep the sleeves in place.

Mid layers

The role of the mid layer – often referred to as the insulating layer – is to retain the body heat you generate and keep you warm. This works by trapping warm air in thousands of tiny air pockets. A mid layer can be any item of clothing worn over your base layer and under your outer shell, such as a synthetic gilet, micro-fleece hoodie or down insulated jacket.

Down jacketsprovide a superior warmth-to-weight ratio, but they are expensive. Synthetic jackets provide better value and improved insulation when wet, while fleeces are generally heavier and cheaper but deliver far better breathability.

Choosing the right mid layer for you will depend on the type of conditions and activities on your schedule. In the height of winter, thicker and warmer layers – such as a puffy down jacket – are likely to be required. In milder conditions, a lightweight microfleece with less insulation may suffice. Or, for improved versatility, it might be wise to carry two or more mid layers of varying fabrics and thicknesses.

On top of insulating you, a mid layer also needs to assist with the movement of moisture from your body to the outside of your clothing, in conjunction with the base layer. Lightweight fleeces are generally better at this, because they are naturally permeable.

Synthetic and down jackets are so good at retaining warmth that it’s actually easy to overheat, therefore they are perhaps better suited to times when you’re still – in camp or at a summit – rather than when you’re working hard and require better breathability.

Recommended hiking mid layers:

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

Constructed from a technical jacquard fleece with a unique zigzag texture, the R1 Air Full Zip Hoody provides warmth, breathability, and moisture management in one. A superb layer for mountain activities, the slim fit keeps bulk to a minimum for easy layering.

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

A versatile mid layer made from performance stretch fleece, the moisture-wicking fabric provides lightweight warmth and optimal mobility.

Outer layers

The outer layer is a waterproof and windproof layer designed to protect you from the effects of rain and wind. Most commonly this is in the form of a hard shell waterproof jacket, often utilising a Gore-Tex membrane or a brand’s proprietary technology.

The sole purpose of such a layer is to keep you dry, so it’s important to gain an indication of how waterproof a certain product will be. Do this by checking the hydrostatic head (HH) rating – the technical measurement of waterproofing. If you’re likely to encounter heavy and sustained rain, opt for a jacket with a 20,000mm HH or higher, which means a 20m column of water can stand on the fabric before water penetrates it. For gentler showers, a lighter-weight jacket with a lower HH rating will work fine.

The big downfall of waterproof outer layers is that they can feel clammy and sweat-inducing. The solution, in theory, is to choose a jacket with a high breathability rating. Products with a 20,000g/m²/24hr breathability rating or higher – a measure of how quickly moisture is wicked away from the body and released through the fabric – will offer the best breathability available.

One other option – that diverges from the classic 3-layer system – is to utilise a water-resistant and windproof soft shell jacket or windshirt instead of a hard shell. Such jackets can provide all the protection you need from wind and rain, except in particularly torrential downpours, and may prove lighter, more comfortable and significantly more breathable than a traditional waterproof jacket.

Recommended hiking outer layers:

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

Designed for hiking, the GORE-TEX fabric with GORE C-Knit backer technology protects against wind and rain while maintaining breathability.

www.ellis-brigham.com

Description

Comfortable, protective, and equipped with a practical feature set, this is an excellent choice for wet weather hiking.

Other approaches to outdoor layering

Paramo and Buffalo are brands synonymous with a non-conformist approach to layering. Paramo’s waterproofs – which use ‘directionality’ technology – are warm, windproof, breathable and designed to be used with just a base layer, while Buffalo’s double-p (pile and Pertex) jackets can be worn next to the skin and replace several layers.

Don't forget to subscribe to the Live For The Outdoors newsletter to get expert advice and outdoor inspiration delivered to your inbox!