Ever wondered how your body regulates your temperature and copes while running in hot weather? The truth is, we each acclimatise differently to running in the heat, with some managing better than others. The key is to understand what happens to your body as you run. This includes your sweat rate and how much you need to re-hydrate to stay in fighting, or should we say, running form.

As part of the Run 1000 Miles challenge, we've shared the experience of trail running journalist Paul Halford, who learns how to best analyse sweat output and run performance in hot conditions. Here's what we found and how you can learn from Paul's findings...

Learning how to run in hot weather

The sweat is pouring off me. The temperature reaches 40 °C and my heart rate is telling me I’m doing a speed session. Yet this isn’t the hot Sahara. This is England in late March – when UK seems to get its winter nowadays – and I’m on a treadmill at a supposedly easy pace.

My run was in a heat chamber as part of a ‘Marathon des Sables Experience’ put on by Precision Fuel & Hydration (PFH) at Silverstone race circuit. The MdS itself was due to start in a few days’ time. Hundreds of hardy souls were ready to take on the six-day 250km race across the Sahara desert.

The previous year was a killer edition in which competitors faced up to 65 °C temperatures – not made any easier by a stomach bug going around camp. PFH had initially promised 50°C for my time in the heat chamber. “Sounds horrific. Ok then,” I said as I accepted the challenge.

Why did I agree? Aside from merely experiencing what it was like to run in extreme temperature, the afternoon would allow me to learn about the effect of heat and sweating on my own running and would perhaps enable me to tweak my training accordingly.

So it was with more than a little trepidation that I went along to the Porsche Human Performance Centre (PHPC) at Silverstone. After a quick introduction to the centre and their work from PFH’s Abby Coleman, I headed to the lab.

In the lab

What I naively thought would be a 10-minute treadmill run turned out to be two sessions of half an hour each. The first part of the experiment would be as a control in normal lab temperature: 18 °C.

PHPC lead sport scientist Jack Wilson recorded my height, weight and body composition data and then I did the half-hour at 5min/km (6km) before being weighed again.

As a means of taking a breather, I then underwent a sweat test back upstairs in the office. This was a painless procedure done in minutes without a blood test, using straps applied around my arm to collect samples.

Abby and colleague Greg Thew ran me through a standard questionnaire as I sat there sweating away. “Are you a salty sweater?” I was asked, and I had to admit I was not really sure, despite having run for 25 years.

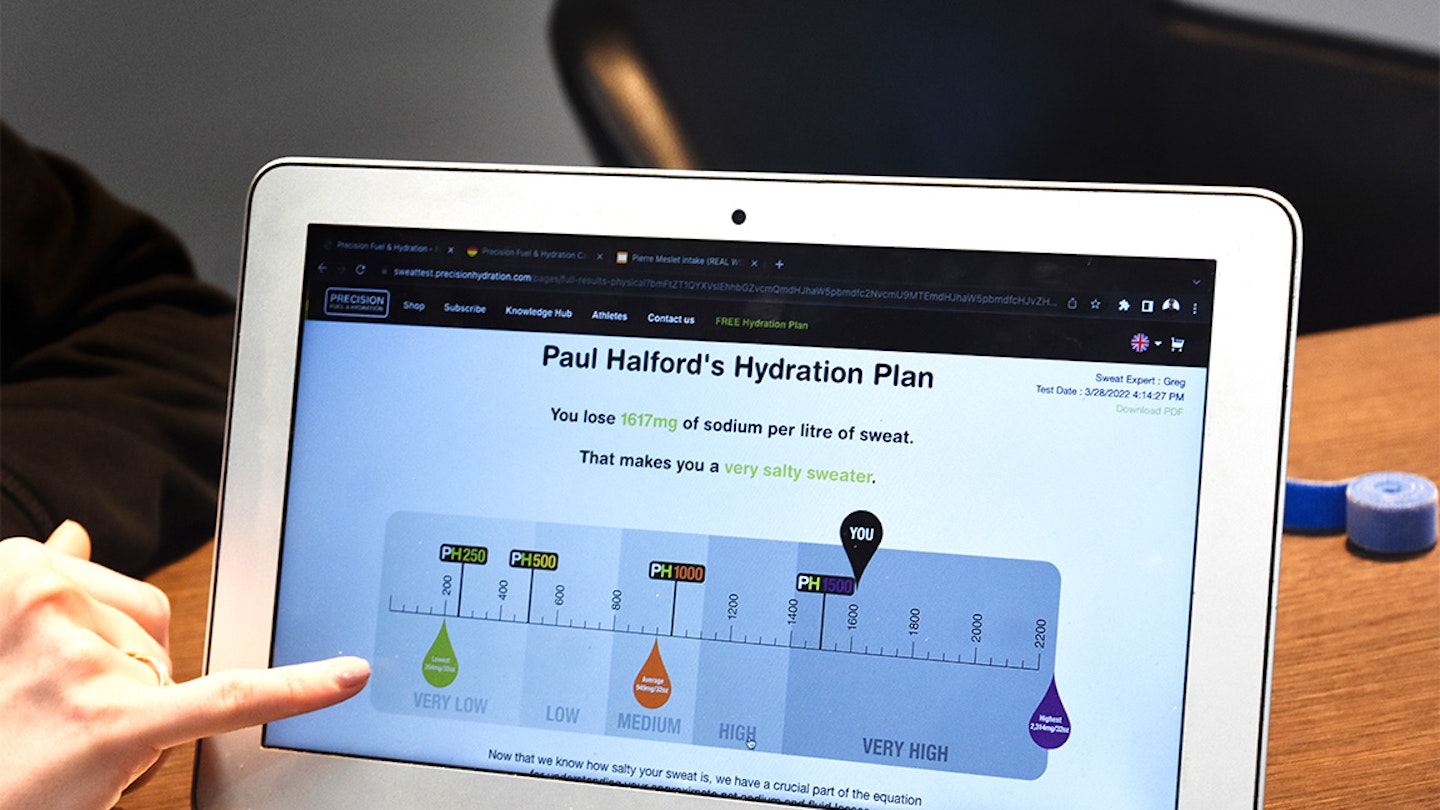

“Does your sweat taste salty or do you get white stains on your skin after a hot run?” Greg asked. “I think so,” I responded. That was confirmed by the small, portable machine analysing the chemicals of my sweat when it showed up the reading – 1617mg of sodium per litre of sweat. That put me at the low end of the very high category – at 70% of the highest PFP have seen and 70% higher than average.

Sodium content of sweat

The sodium content of sweat can vary by more than 10 times between athletes. Indeed, the lowest PFP I have seen is 204mg/l. As you exercise, you’re losing sodium as well as other electrolytes, to a lesser extent, so just replacing sweat like for like with water to rehydrate may not be enough.

Based on that information, I received a hydration plan via email which recommended their PH1500 product before a race and their PH1000 during racing or training. Low sodium levels can hinder your performance.

In everyday life, we will usually have enough, but exercise can deplete it as we are losing it via sweat. Using water alone to rehydrate can make it worse as you dilute your levels. The other thing to bear in mind is how much sweat you lose during exercise, which varies from person to person and, of course according to the temperature.

This can be worked out yourself relatively simply by weighing yourself nude immediately before and after a run. On the initial trial in normal temperature, I lost 400ml over 30 minutes. However, bear in mind that I wouldn’t have been sweating at all for the first 10 minutes or so, so my sweat rate is likely more like one litre per hour.

When I considered I could lose almost 4% of my bodyweight on a two-hour long run – composed entirely of magic ingredients such as water and electrolytes, it made me realise how important it is to think about hydration.

That’s just under the typically comfortable conditions we get in this country. What about in more hostile conditions? I was about to find out! I was genuinely daunted.

In the heat chamber

The very phrase ‘heat chamber’ was perhaps responsible for more of the fear than the temperature itself. “How much danger could I be in?” I asked Jack. The potential results of hyperthermia are very serious, including dizziness, vomiting, seizures or even death.

However, Jack reassured me he would take my temperature every five minutes and pull me out if I went above 39.2°C. The other journalist involved in the study, who was in the chamber just before me, reached 39.2°C at the final check, at 25 minutes.

My general experience in the chamber confirmed I had little to worry about. In fact, I found the heat uncomfortable rather than excruciating. But the stats were more revealing. Between five and 10 minutes in, my temperature soared by 0.9°C – virtually halfway towards the danger zone.

After that, it was more gradual but it crept up and up, so it was at 39°C by 25 minutes. I made it to the end of the 30 minutes but the final reading of 39.2 showed how close I’d gotten.

My heart rate also showed a big leap from five to 10 minutes before a steady progression. By the end it was up to 170bpm. I would expect a peak of around 175bpm when doing a set of speed intervals but here I was doing an easy pace.

Getting the results

I produced 650ml of sweat in the heat test compared to 400ml in the control, mostly in the final 20 minutes. I had always considered myself to be a reasonably good performer in the heat. Others had told me this, and I also noticed doing better than expected against my peers in hot races.

However, there was nothing here to suggest that was the case. This was after just half an hour. If I had run for longer, at some point I would have had to ease up, stop, or cool myself down somehow.

Our bodies’ cooling mechanisms are remarkable. The way humans sweat makes us best suited of all animals to long-distance running. But there is only so much we can take.

UK-based Frenchman Pierre Meslet had been advised by PFH on his way to ninth in that horrific MdS of last year. He joined us by video call at Silverstone to talk about what he surprisingly described as an “awesome” experience – just as I was still recovering from my own half-hour in Saharan temperatures.

The experts explain

He explained: “What I struggled with was the cooling down. You had to take more water than normal, so you had to use some of that on the head, the neck and arms because the body temperature was going through the roof quite quickly.

“When you look at 56°C and 3% humidity, it sounds horrendous but when you’re out there and a little bit used to the heat for 10-14 days, your body sweats a bit differently. Less salty, a bit quicker sweating, and just more comfortable in that environment.”

His carefully calculated hydration plan was crucial, he believed. “I thought it was essential to my success even more so as it was such a hot year,” he said. Perhaps you’re not about to run across the Sahara, but most runners could benefit from learning more about their sweat.

Making sure your body has enough electrolytes and is adequately hydrated is vital, but even when you’re not racing it can be crucial for recovery. If you pay attention to the details of hydration, performing to your best – even in the heat – could be no sweat!

How to measure how much you sweat

Testing in a lab is always the ideal but it’s not too difficult to get a good estimate of your sweat rate at home. Here’s how...

1. You are going to weigh yourself immediately before or after a run since this will closely tell you your sweat rate. 1L of water (or sweat) weighs 1kg.

2. Choose a run of between 60-120 minutes. Anything shorter or longer could skew the results a little because you don’t sweat much for the first 10 minutes, and you sweat at a different rate by the end of a long run.

3. Weigh yourself on both occasions, ideally nude to avoid sweaty clothes affecting the results. Dry your body and particularly your hair afterwards to remove as much of the sweat as possible.

4. Take 2-3 readings on the before and after until you get a consistent reading. Digital weighing scales can be inaccurate when you first move them and put them down on the floor.

5. Record any fluid consumed between the before and after weigh-ins. This can be done by weighing your bottle before and afterwards. Remember, 500ml equals 500g.

6. If you have to urinate, take another recording of your before weight. The test will be invalidated if you pee during the session or before the after weigh-in.

7. Your sweat loss in litres = (weight (kg) before + weight (kg) consumed during) - weight (kg) afterwards.

8. Your sweat rate per hour = sweat loss ÷ hours training.

Meet the expert

Jack Wilson is lead sport scientist at the Porsche Human Performance Centre, where he provides athletes with lab-based performance testing and heat acclimation, as well as nutritional advice.

Top image credit: Brian Erickson

Don't forget to subscribe to the Trail Running Newsletter to get expert advice and inspiration delivered to your inbox.

This article is brought to you by the official Trail Running Run 1000 Miles Challenge.