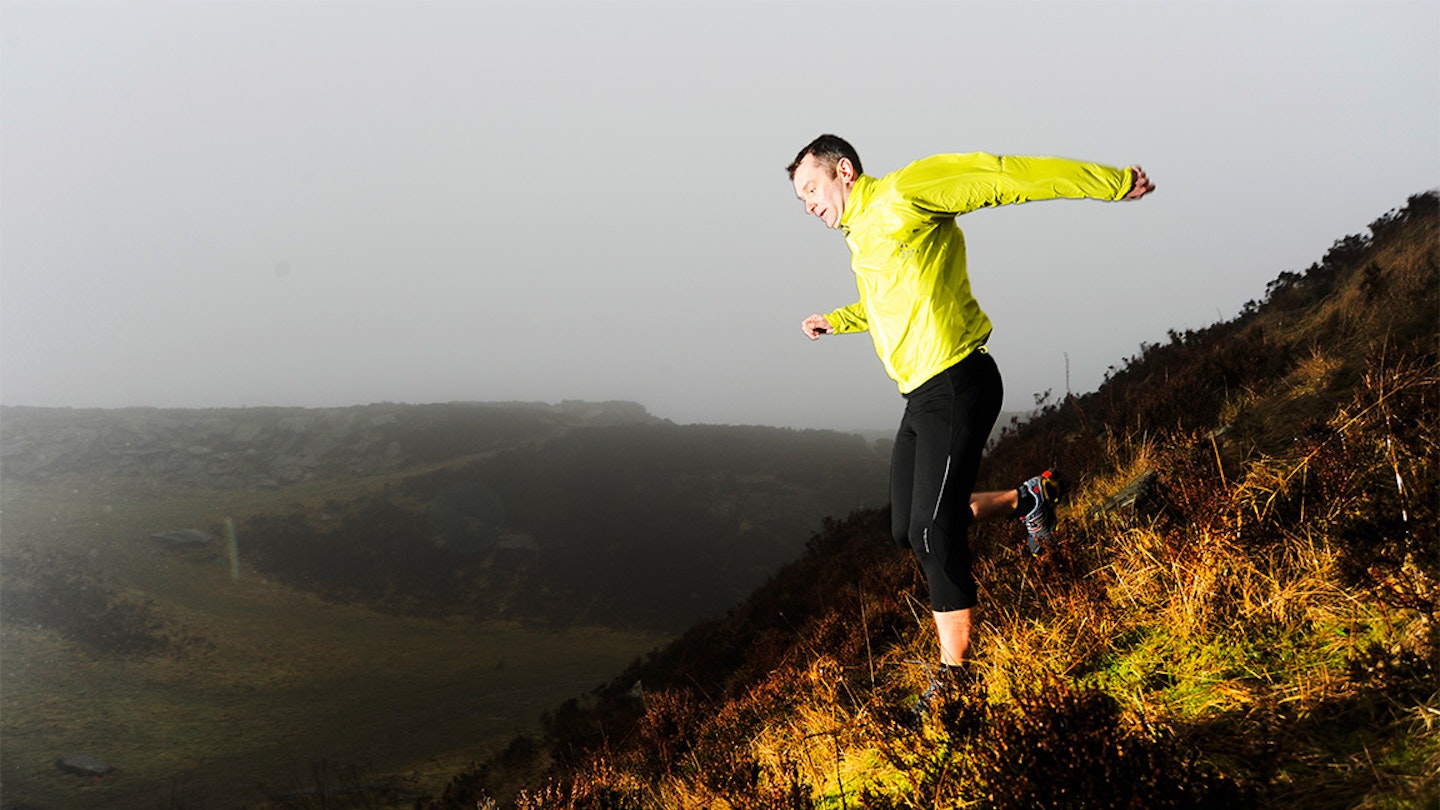

Professor John Brewer takes an in-depth look at exactly what happens to your body at every stage of your run, and the multitude of benefits that make every step of the journey worthwhile.

Shall I or shan’t I? That’s a question that almost all of us will have faced when you just can’t decide whether putting on your trail running shoes and going out for a run is really worth the effort.

It often seems far easier to stay indoors, particularly if the weather is bad, and curl up in front of the TV or computer, rather than heading outside to face the physical exertion of running. The key to answering the “shall I or shan’t I” question lies in motivation.

Over the years, as a sports scientist, my personal motivation has come from an understanding of the physical and mental benefits that running brings. These benefits apply to anyone, regardless of age and ability, so this article sets out to explore what happens to our bodies and minds both during and after a run, and hopefully helps to make “I shall” rather than “I shan’t” the preferred answer to the question of whether you should lace up and get out.

But firstly, it’s worth exploring what will happen to your body if you don’t go for a run. Perhaps not surprisingly, not a lot.

What happens to the body at rest?

Your heart rate will remain at around 70 beats per minute, you will continue to expend about three calories of energy per minute, around 12 litres of air will enter your lungs each minute, and your oxygen uptake will be at about three millilitres of oxygen per kilo of body weight.

Or, to put it another way, your body will remain sedentary and at rest, and is only called into (slight) action when you move around the house or press the TV remote control.

But if you do decide to go for a run – and let’s assume it’s an 8km trail run – the implications for your body and mind are vastly different and way more beneficial than staying indoors.

How does running change your body?

Changing into your running gear, and putting on your running shoes, is the first part of the process. You will already be starting to mentally prepare for the run ahead and will soon experience a slight increase in heart rate, adrenalin, and blood flow to the muscles in preparation for the imminent run. This is an inherent “fight or flight” response that we all have, as the body sub-consciously prepares for action, and is the same response that our ancient ancestors had when faced with a predator.

Getting going: kilometre 0-2

The first few strides are often the toughest. Muscle temperature is still low, and the supply of oxygen to the muscles will take time to match the rate at which it is needed to produce energy. For those first few seconds, some energy will be produced anaerobically – without oxygen being present – which in turn will result in fatigue-inducing lactic acid.

Consequently, the early part of any run can feel quite tough, even if you have set off reasonably slowly. The body is taking time to adjust to the exercise that it is doing and its higher rate of energy expenditure.

Ventilation rate – the volume of air going in and out of the lungs each minute – will soon start to increase, initially by taking deeper breaths, and then by taking more frequent breaths. About one fifth of the air going into the lungs consists of oxygen, and in response to the body’s desire for extra energy, some of this oxygen passes through wafer-thin membranes in the lungs, and into blood vessels surrounding the lungs.

Once in the blood, oxygen attaches itself to a molecule called haemoglobin, and is ready to be pumped around the blood stream to the muscles or other vital parts of the body. The pump doing the hard work is of course the heart, and from a resting value of around 70 beats per minute, it will quickly increase to 150 beats per minute – or even higher – to force blood and oxygen around the body.

At rest, around five litres of blood will be pumped through the blood vessels by the heart each minute; but during exercise this can quickly rise to between 20 or even 30 litres a minute – similar to the volume of fuel going into your car when you fill up at a petrol pump!

When haemoglobin and oxygen arrive at the muscles, which are already working hard to support each running stride and propel the body forward, oxygen molecules separate from haemoglobin, and enter the muscle where a highly complex biochemical process takes place involving the body’s reserves of carbohydrate and fat, to provide much needed energy for running. It sounds simple, but it most certainly isn’t!

So, what is immediately apparent is that the physiological demands of running greatly exceed the demands that are placed on the body when at rest. The good news is that the human body is designed to exercise – those ancestors of ours had to run to avoid being a predator’s next meal, but modern lifestyles have meant that, for many, the capability that we have for exercise is rarely exploited.

But after just the first few strides of a run, we are already starting to unlock our potential, using our muscles, lungs, and heart in the manner that they have evolved for, and which ultimately will make them healthier and stronger. The commonly used adage of “use it or lose it” really does apply, and by asking the heart, lungs, and muscles to work a bit harder than normal, they will quickly adapt, get stronger and healthier, and be less likely to fail.

The early stages of a run: kilometre 2-4

By this point, most runners will have reached a “steady state”; the oxygen supply to the muscles will match the rate at which it is needed to provide energy, and whilst heart rate and breathing frequency will have increased, they will have reached a plateau, having stopped rising any further.

One of the consequences of muscles producing the energy we need to run is that they also produce heat, and this heat soon starts to increase body temperature. At rest, most of us will have a body temperature of around 36-37°C, but this soon rises when we are running.

If left unchecked, temperature will continue to increase, and hypothetically, even a moderately paced run could cause body temperature to reach boiling point within 12-16km of running unless there is an efficient way of losing heat.

By the second kilometre of a run, body temperature will have risen by one or two degrees, but our preferred heat loss mechanism – sweating – should have kicked in. Subconsciously, our skin pores excrete fluid – our sweat – which then evaporates from the skin surface into the external environment.

It is this process of evaporation which causes heat to be lost, and which maintains control of body temperature. At the same time, and as an additional way of losing heat, blood is diverted towards the skin, which explains why many of us runners tend to take on a red complexion during and after a run, especially when conditions have been hot.

The middle of a run: kilometre 4-6

By this stage, the run is well under way, and the body will be reacting to different gradients and challenges. Trail running is great for developing core stability, as the undulating ground means that we must continually react to changes in our centre of gravity caused by uneven terrain. The abdominal and trunk muscles will be supporting the body by contracting and relaxing in response to the ground, ensuring that runners retain stability without falling over.

No trail run is complete without hills. Hills mean fighting against gravity, and put extra strain on the leg muscles, particularly the quads and the calf muscles. This overloading is good news, as it causes the muscles to gain protein and increase in strength. Of course, this won’t be of any benefit on this run, but it will have benefits for future runs and hill running ability.

Running downhill also has a great training effect, albeit with the potential for painful consequences! When we run downhill, our quad muscles in the thighs are stretched with each stride to absorb the impact created when the striding foot hits the ground.

It may seem counterintuitive, but despite stretching, the quad muscles are also simultaneously trying to contract – if they didn’t, the legs would collapse due to the impact forces from each stride. Scientists have shown that a muscle trying to contract whilst being stretched – otherwise known as an eccentric contraction – will develop extra strength relatively quickly when compared with “normal” contractions.

Consequently, the downhill sections of a trail run are actually a great way of developing leg strength, providing care is taken and speed is controlled. However, one side effect of eccentric muscle contractions is increased muscle soreness, which is linked to inflammation and pressure within the muscles as a result of the work they have had to do. The first 24-48 hours after a hard run are often the worst in terms of soreness, but the “damage” is a precursor to repair, and even stronger muscles in the future (provided you don’t push too much and injure yourself!).

The end of a run: kilometre 6-8

As we head for home towards the end of the 8km run, there should be some fatigue in the legs, almost certainly linked to an increase in lactic acid, rather than a depletion in energy stores.

There will be some dehydration as a result of losing fluid from sweating – if the run has taken around 30-45 minutes, one or at most two litres of sweat will have evaporated from the body, and this fluid-loss should be replaced as soon as possible after the run has ended.

Even on the hilliest and toughest of runs, total energy expenditure should be no more than 600-700 calories, way below the body’s total stores of glycogen (the energy form of carbs), so energy depletion should not be an issue.

Unless aiming for a PB, it’s sensible to use the last part of a training run as a cool down, slowing starting the process of returning the body back to a sedentary state. If you are trying for a PB, tag on an extra five or 10 minutes of running after you have finished as part of a warm down.

Recovery time

You may have stopped running, but your body will still be in overdrive. It will take some time for your body temperature to fall, so you will still be sweating for a while after you have finished, and your breathing and heart rate will be higher than normal for a few extra minutes. Now is a good time to stretch, as your muscles will be warm and supple, and stocking up on fluid to rehydrate should take priority over re-fuelling.

Top image: Andy McCandlish

For all the latest news, tips and gear reviews, sign up to the Trail Running Newsletter.