Do you remember that scene in Blackadder (series 2, Money), where Percy creates ‘a nugget of purest green’? Well, I’m in search of a whole glen full of the stuff. And by ‘green’ I mean the Scots pine trees of the old Caledonian pine forest.

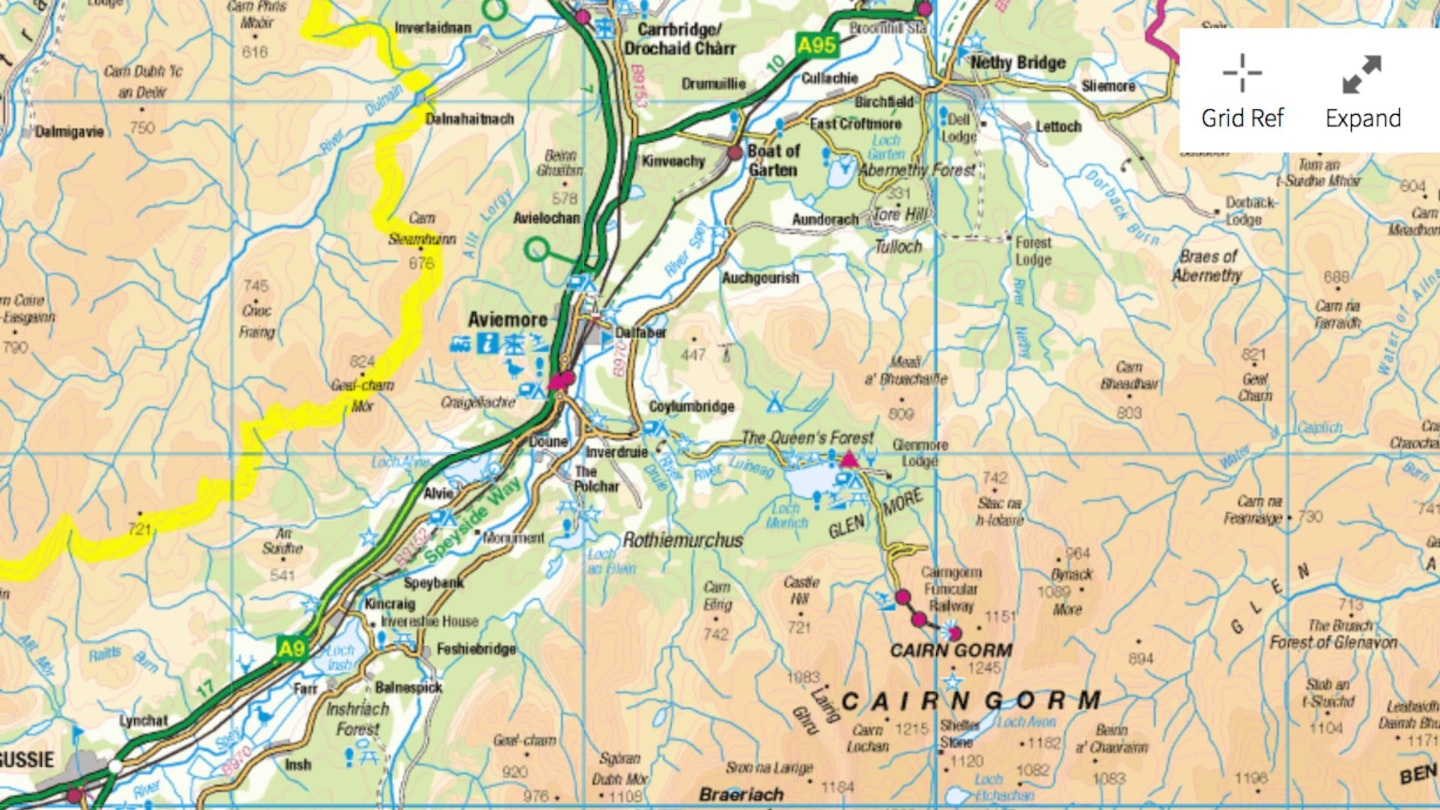

Open an Ordnance Survey Explorer 57 map and you can’t miss it – a big green eye with a blue pupil staring out at you. That vast area of green is a combination of the Rothiemurchus Forest, the Queen’s Forest, Glenmore Forest Park and the Glenmore National Nature Reserve – all linked together in a largely plantation-led biblical flood of green.

The blue is Loch Morlich. I can almost hear your mind turning: ‘What’s so great about walking through endless miles of plantation?’ I completely agree, but in this instance it’s a case of not being able to see the wood for the trees.

In amongst those endless acres of lodge-pole plantation, there are gems. Pure, unrefined, priceless jewels. They are wild, fully-formed Scots pines. Finding a hillside of these elders is the summit I’m seeking. For in this modern world of goal-driven madness there’s a place where you can slow down the world. Maybe Percy wasn’t so wrong after all, for the green of nature is where true wealth lies.

Scotland’s ‘Great Wood’

For years now, I’ve visited the Cairngorm mountains. Yet, despite a love of woodland I’ve spent precious little time in the Caledonian pine forest. There are times in your life when you need a little reconnection and this is one of them. I have two whole days ahead of me, and a night alone in the woods.

The Great Wood of Caledon was a Scots pine forest that originally (after the last Ice Age and before man exerted any influence over it) covered the whole of the central Scottish Highlands. Tree cover was at its zenith around 3000BC. Various theories abound as to how and when this natural resource started to diminish.

It seems that by Roman times five-sixths of the wood had been destroyed, burnt down in the Viking wars or cleared to deter wolves, and then in later times was felled by English businessmen. What is sure is that this landscape – and by that I mean Caledonian pine woods – have a dramatic history when it comes to humankind.

There are said to be around 100 of these forests in Scotland: in the east they follow the rivers Spey and Dee; while over on the west coast, the Applecross/Torridon area boasts a few. As in other parts of the country, post-World War One plantations abound and account for the vast majority of pines in Scotland.

All is not lost. The story, as far as these trees in Scotland is concerned, is by no means finished. Rewilding, reforesting projects are happening in many areas, both due to the influences of individual land owners and national conservation bodies. The future is green.

Into the wild

The north-western corner of Loch Morlich makes the transition into woodland slowly. An area of marsh makes the western shore indistinct and impenetrable. This means few people access the area, even though it's accessible from Aviemore, and wildlife flourishes.

There’s a theme here: impenetrable. Whether it’s plantation or that Holy Grail of true, tangled, chaotic forest, progress off the paths is hard. For this reason, using the many forest tracks is necessary to make progress. But remember this isn’t a race, it’s about immersion.

Over two days I only want to cover about 30km. Remembering walks of my past, the Lairig Ghru path passes through some fine areas, so it’s the start of this route – up to just under the pass itself – that I take. Lochan nan Geadas stops me in my tracks, and my knees buckle.

Approaching this plantation-swamped pool, an island is visible and on that island there are four or five grand old masters. Their limbs reach in every direction as a free tree should, jostling with their neighbours in nature’s efficient way.

They contrast so starkly with the ranks of orderly plantings on the mainland. The sight is both beautiful and tragic, making me realise just how dramatic a whole glen’s-worth would be. If only.

Even though I’ve walked less than 1km, a break is called for. There is so much to take in. The connection is beginning. Life buzzes. Dragonflies chase smaller insects. Backlit against the dark canopy, they tremble and sparkle in an ever-changing and transient way. Crossbills call and restlessly flit from treetop to treetop. A specialist bird of this woodland, it’s the first of the wildlife spectacles I’d hoped to see.

A piece of the forest

Without it consciously happening, I realise I’ve dressed almost entirely in green. I clearly wanted to not only visit this place, but also to be a part of it. The route pulls up towards the mountain pass. Amongst the trees, climbing a hillside seems the easiest thing in the world. Out in the open, the views often don’t change for miles and miles. Here, every few metres things are different.

Three or four kilometres in and there’s a dramatic change in the number of old trees I’m seeing. Looking the nearest one up and down I see roots spilling from the earth to form the trunk. This is covered in large, blotchy plates of bark that resemble the marks on the neck of a giraffe.

From roughly head height, branches jut towards me. They grow with every contortion imaginable, seeking light. The higher up the tree, the younger the branches, and the redder the bark becomes. One or two limbs have died and remain, pale and stark, lacking the green light-absorbing needles that the living branches are crowned with.

I never think of a tree growing upwards, more dangling down, with the roots being the top of the tree, anchoring it into our spinning Earth. From that rock-solid base they drip into the air with stalactitic speed, spreading their ever-thinning fingers into every corner of the air. Laying under a tree, looking up the trunk, I remind myself about gravity. For a moment it feels like I’m about to fall into the sky.

Shortly after this mind-bending episode, another irritant reminds me I’m ground-bound. Wood ants are all over me. Our largest ant species, they form huge mounds made out of pine needles which are easily spotted once you get your eye in.

There aren’t many points in the day when I look down and don’t see the ground seething with them, like I’m on some dark Amazonian adventure. Luckily, they do me little harm – the substance they secrete when handled even smells like salt and vinegar crisps.

The eye of the storm

Rain pitters down in the late afternoon. It’s not a problem, as the pines provide shelter. Loch Morlich, the blue eye in this storm of green, provides me with water for a cup of tea. Water, trees, mountains – that holy trinity, that prehistoric idyll, ruined by the success of humankind.

Sat by the shores I feel I have everything I could ever want. I wake with my tea cold but a new, sharp, hunger. Not for food, but for the forest. I pack and am on my way in minutes. I feel tuned in, refreshed, energised. The sun falls through the branches, warming my face. I’ve found something, something I’ll never lose.

A small lochan on the map intrigues me. I need somewhere to bivvy tonight and clear spaces in the forest are surprisingly few. A hammock would have been ideal, but I hate hammocks.

Nearing the water, I pass through the infrared beam of a pedestrian counter. Even here, deep in a pine wood on the side of a mountain, I’m being monitored, counted. The lochan is a surprise. Black water, surrounded by a pristine array of trees and plants, it feels as if no human has ever set eyes on the place.

Yet it is mere metres from a forest track. I make my main meal of the day and sit on the bank looking down into it. I know I will not sleep here, I knew it the moment I saw the place. I won’t dilute the purity of the place. I leave without even breaking a grass stem, the counter checking me out.

Night under the stars

An Lochan Uaine is the place I choose for my night under the stars. The breeze is steady, if a little on the cool side, but I’m thankful for it as it’s keeping the midges away. Pines fringe the aquamarine waters, two of them preventing me from rolling into those cool depths in the night, should I spin over in my bivvy.

I’ve been up and about in the woods for 12 hours solid now. My mind and body both need rest, in fact so much so that when three people (two women and a lucky chap) arrive at the other end of the lochan, strip off and frolick in the water, I hardly notice. I just turn on my side and sleep one of those deep, outside sleeps that come so very rarely.

Darkness never fully arrives, as it’s June, but the bright skies aren’t a problem and I’m fast asleep in the early hours. I open my eyes to the same intensity of light as when I closed them.

I can see the early sun hitting mountaintops. Snapping into action, with everything packed away, I head through the lower pines on the southern flank of Meall a Bhuachaille. The weather is holding. The path I’m on climbs but doesn’t quite give me the all-encompassing view I’m looking for.

I break from the path, pushing through kneehigh heather and bilberry, bees lifting before my boots, the sweat overloading my eyebrows and flooding into my eyes. I push on and up to what I think will give me that memory, that crystalline moment I want to trap forever.

Off path the going is hard. The vegetation varies from a few inches to a couple of feet tall. The ground underneath is a maze of humps and hollows, with tree roots snaking into the mix.

A view to remember

Finally I’ve found my summit. The journey through the Caledonian pine forest of the Cairngorms has reached some kind of crescendo. A small heather-covered ledge, framed by a character pine, open to the morning sunlight, is the setting for a view fit for an eagle. Dropping from my feet, pines spill down the mountainside, carpeting the wide valley floor, consuming everything other than water.

This tide peters out on the lower flanks of the Cairngorm mountains, giving the illusion they’re some mystical land far away from humankind. I’m seeing the Cairngorms in a way that I wanted to see them. I’ve made this moment happen and it means something very special to me.

An hour passes, the sun has climbed, clouds threaten, the window is closing, but I’ve reached in through the broken window of the morning and snatched the moment I needed. I feel wild, like I’ve hunted this fragment of time, hanging it with the others in the larder of my mind.

There is only one thing for it: a coffee. Down at the base of the mountain I find a café just opening. The caffeine fires through my system, helping me to relive those moments, fixing them deeply. More forest follows. Plantations come and go.

In an area of clear-felled plantation, a group of long-dead ancient pines look as if they’re locked in some tribal meeting, oblivious to the comings and goings of time. The mountains provide an epic backdrop.

Nearing the end of my journey I notice a sculpted wooden owl sporting a lost hoody. I love people with a sense of humour, and this moment somehow trips me back into a 21st century way of thinking. I’m ready to leave the trees, my internal balance has been recalibrated. Give me some mountains.

Rothiemurchus: A brief history

The name Rothiemurchus dates back to the 8th century, with the earliest inhabitants thought to be Picts. The Parish of Rothiemurchus belonged to the monarchy until 1226 when it was passed on to the Bishop of Moray until the 16th century. In 1574 Patrick Grant was given the title ‘of Rothiemurchus’ by King James VI, and this Highland estate has been under the stewardship of the Grant family ever since.

Liked this? You might also be interested in how to identify mountain trees, or 7 reasons you have to walk in the Cairngorms.

Local lexicon

Many Cairngorm place names have evolved and adapted over centuries. Here are some of their suggested origins:

-

Rothiemurchus: ‘The Great Plainof the Fir’

-

The Cairngorms: ‘The russetcolouredmountain range’

-

Loch an Eilein: ‘The loch ofthe island’

-

The Lairig Ghru: ‘The pass of the(river) Druie’

-

Gleann Einich: ‘The glen ofthe bog’

-

Breariach: ‘The grey-brownspeckled upland’

Wildlife watch

The Cairngorms National Park is home to 25% of Britain’s threatened animals. Here are some key species to look out for in Rothiemurchus:

-

Capercaillie

-

Pine marten

-

Crested tit

-

Scottish crossbill

-

Wildcat

-

Golden eagle

-

Osprey

-

Red squirrel

-

Red deer

-

Mountain hare

About the author

Tom Bailey has been Trail magazine’s photographer for more than 20 years and is one of the most experienced hillwalkers and wild campers in Britain. He’s climbed more mountains than most people could dream of and is an oracle of knowledge on everything from routes and gear to geology and nature.