Whether you’re training for a race or just trying to get fitter, understanding your effort level is crucial. One of the most effective and accessible tools for this is Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) – a simple way to measure how hard you’re working without relying on gadgets.

In essence, this is about how hard you feel you are working when running. Are you giving everything you’ve got, drool and snot all over your face, desperately hanging on? Or, are you barely breaking a sweat? Maybe you're somewhere in-between, in which case, you're on the right track!

It’s that range of ‘feel’ that RPE attempts to quantify. Taking a qualitative measure – how hard an athlete is working as perceived by the athlete – and turning that into a quantitative one.

It can be used both by an athlete to describe how challenging they found a session, and by a coach or training plan to give guidance on how challenging a session should feel.

It’s also useful to see progression of a training plan, i.e. how did this week’s session feel relative to the same session you did four weeks ago? Maybe you’ve done this at the end of a run already on your sports watch, y'know, by hitting the smiley face or the crying frowny one.

It’s the same principle, requiring the athlete to assign a rating of effort based on some typically subjective sensations such as how hard they are breathing, their heart rate (typically unmeasured), fatigue levels, sweat, and the desire to stop or give up.

What is the Borg scale of RPE?

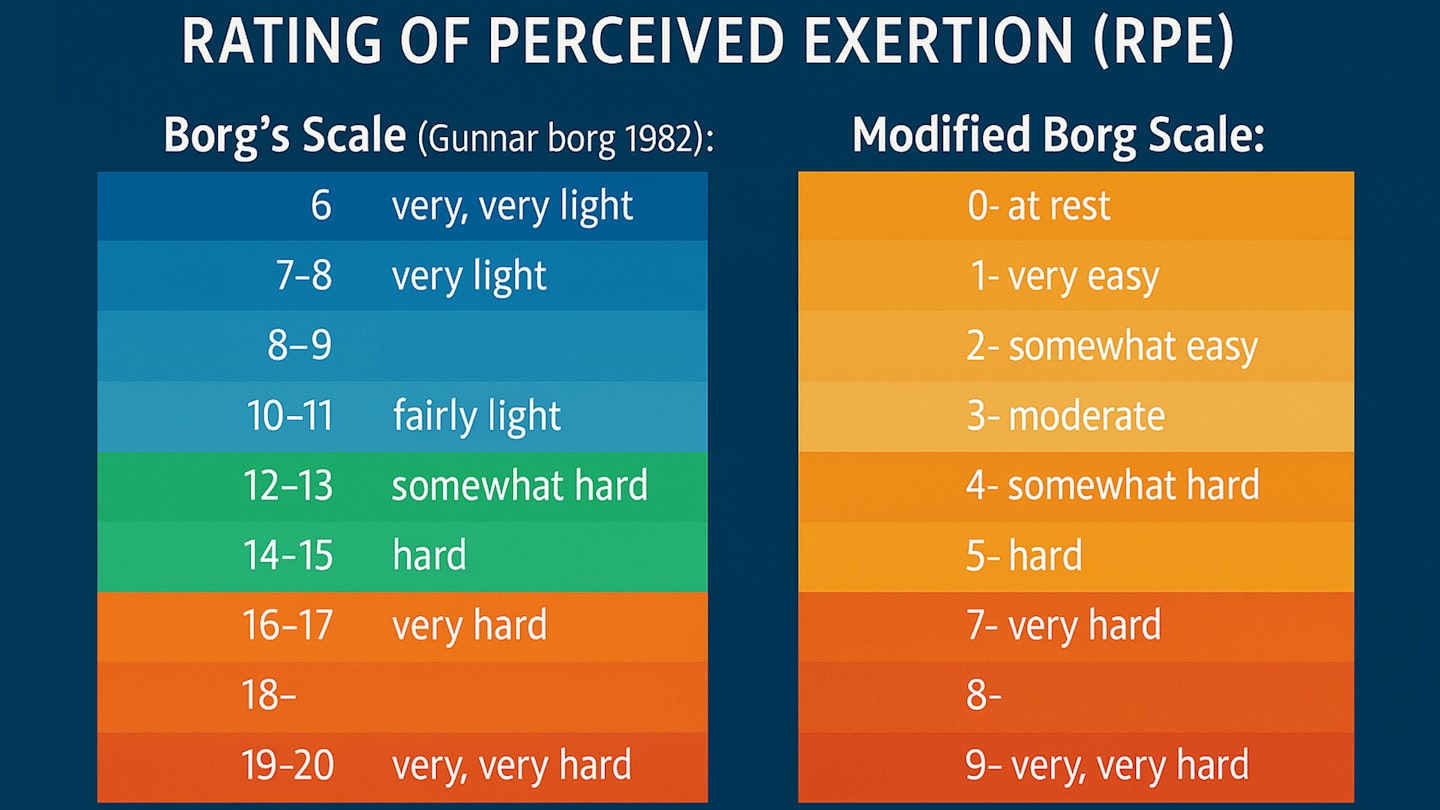

In 1982, a Swedish researcher, Gunnar Borg, came up with a scale used both in the medical field and sports field to denote exertion levels. T

he original scale was 6–20, which may seem an unusual start point, but it correlates to the level of a 20-year-old male’s average heart rate, where 60 bpm (6) = no exertion/rest, up to 200 bpm (20) = maximal exertion/very, very hard, with a linear scale in between—hence the Borg scale of RPE. There is a modified Borg scale (CR-10) with a scale of 0–10, which has more recently replaced the original 6–20 scale.

How useful is RPE for training?

Like any measure used for training, there are some pros and cons. Clearly, the RPE is subjective—but does it accurately reflect the physiology?

The short answer is yes. Although RPE is subjective, research has found a reliable relationship between RPE and physiology, and in certain conditions, a high correlation. These were during maximal exertion—for example, a VO2 max test—or when a less familiar exercise was practised.

Therefore, our intrinsic version of reality does correlate to the workload we are putting our body through. In fact, a study in 2017 demonstrated that there was little difference in the results between an RPE- and HR-based training plan. However, for less experienced athletes, the HR plan was more accurate.

Which takes us nicely onto the caveats. RPE only works well if you know yourself well. The athlete needs to have a history of the exercise and the feeling of the physiological sensations across the full range. How you feel from day to day can impact the RPE, as can medical conditions. For a lot of people, the scale is just too broad. Think of the pain scale—could you define pain 1–20? Most people just about manage 1–5 or 1–3, so perceived effort in this level of detail takes practice.

How can I use RPE in training (and racing)?

As athletes (and by athlete I don’t mean only those of Olympic-level standard, I mean EVERYONE who puts on a pair of shoes to hit the tarmac or trails), the focus on improvement has become more accessible to all.

With the likes of coaching apps, sports watches and just greater awareness, where once the idea of improving was focused on increasing mileage, now there is a plethora of data available to suggest running hard runs hard, and easy runs easy—and this results in greater benefit than just ticking off miles.

Very few of us have regular access to a lab, which means our only ability to quantify or qualify the challenge of our training is through data available on our running watches – and ourselves.

Watches give us a few useful metrics to be able to compare one run against another, such as how fast we are going (but I’m going up a really steep hill so no wonder I’m running slower), what our HR is (but on these 100-metre reps, my HR doesn’t spike until after I’ve finished the rep), how far we have gone (but I was running on sand where every step I took forwards, I slid back half a step)… you get the idea.

Without context, the stats don’t stack up. How else can we assign a value to the difficulty of a run, when we are running in dynamic environments and the variables are difficult to quantify?

That’s where RPE comes into its own.

Anecdotally, I have asked some of my coached athletes to run on a flat surface and go through the range of paces that equates to a 1–10 effort level. Not an exact science, as the athletes fatigued a little as the session went on, but it was clear that even the more experienced runners were not able to distinguish 10 different pace targets on feel alone (without looking at their watches).

A practical application of RPE

The main challenge of using RPE effectively is getting the granularity of the scale versus feeling. There are two things that people can do to improve its use. First, look at the graphic of the RPE scale (see figure above) and either annotate personal descriptions or look them up.

Second, simplify the scale. Start with three zones—from easy through to moderate, moderate through to hard, and then hard through to maximum effort. As a way of understanding the training zones futher, I tend to use the ability to talk as a way of guiding newer runners.

Zone 1 – Talking is easy; you can hold a conversation

Zone 2 – Talking is more challenging but still possible. You can talk but not fluidly

Zone 3 – At the very most, you can say one word at a time, but that’s it.

What does a training plan using modified RPE look like?

Training plans can be intimidating for a beginner runner. Words like tempo, speed, interval, easy, long run, fartlek aren’t that intuitive, so require a reasonable explanation from a coach anyway. Using RPE can be an efficient way of explaining the different effort levels required.

Both coach and athlete have a personal understanding of what something feels like, and the information conveyed by RPE transfers much more tangibly to someone’s experience rather than just looking at, say, pace, HR or some other stat.

For example:

– Easy run: 30 mins – RPE 2–3

– Speed sprints: Warm up, then 100 m at RPE 10, 2 mins recovery × 10

– Tempo run: 10 mins warm up, then 20 mins at RPE 6–7

– Long run: RPE 2–3 for 2 hrs

Conclusion

Overall, RPE is a useful tool for experienced athletes who have a good internal sense of what different intensities feel like. I would suggest for less experienced runners, simplifying the Borg scale to just three zones.

That way you can build up your understanding of how you feel versus output during a run. Noting this down over time will give you a great reference point of progression, and using RPE will sharpen any existing training plan you are currently following. Try it!

References:

-

Research indicates that there is a higher correlation of RPE to physiological factors, under certain conditions. The highest correlations between RPE and the various physiological criterion measures were found in the following conditions: when male participants were required to maximally exert themselves (VO2 max testing), when the exercise task was unusual (such as swimming, which is less common than walking or running), or when the 15-point RPE scale (measuring blood lactate concentration) was used. (MJ Chen, X Fan, ST Moe, Journal of Sports Sciences, 2002, Taylor & Francis).

-

A study by Johnson, Evan C.1,2; Pryor, Riana R.2,3; Casa, Douglas J.2; Ellis, Lindsay A.2,4; Maresh, Carl M.2,5; Pescatello, Linda S.2; Ganio, Matthew S.6; Lee, Elaine C.2; Armstrong, Lawrence E.2. Precision, Accuracy, and Performance Outcomes of Perceived Exertion vs. Heart Rate Guided Run-training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 31(3): p. 630–637, March 2017. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.000000000000154. Indicates that over a 6-week period, there was no discernible difference in results following an RPE-based plan over an HR-based plan, although the data suggested that for the less experienced, the HR plan improved precision and accuracy (although not performance).

About the Author

Karin Voller is an experienced ultra runner, frequently gaining podium positions in popular ultra runs and multi-day ultras in the UK. She was first GB female over the line on the longest stage of the Marathon Des Sables 2011 & 11th female overall. She is also Head Guide at Run the Wild and is a qualified running coach. Her other passion is her two dogs Bailey and Lottie.