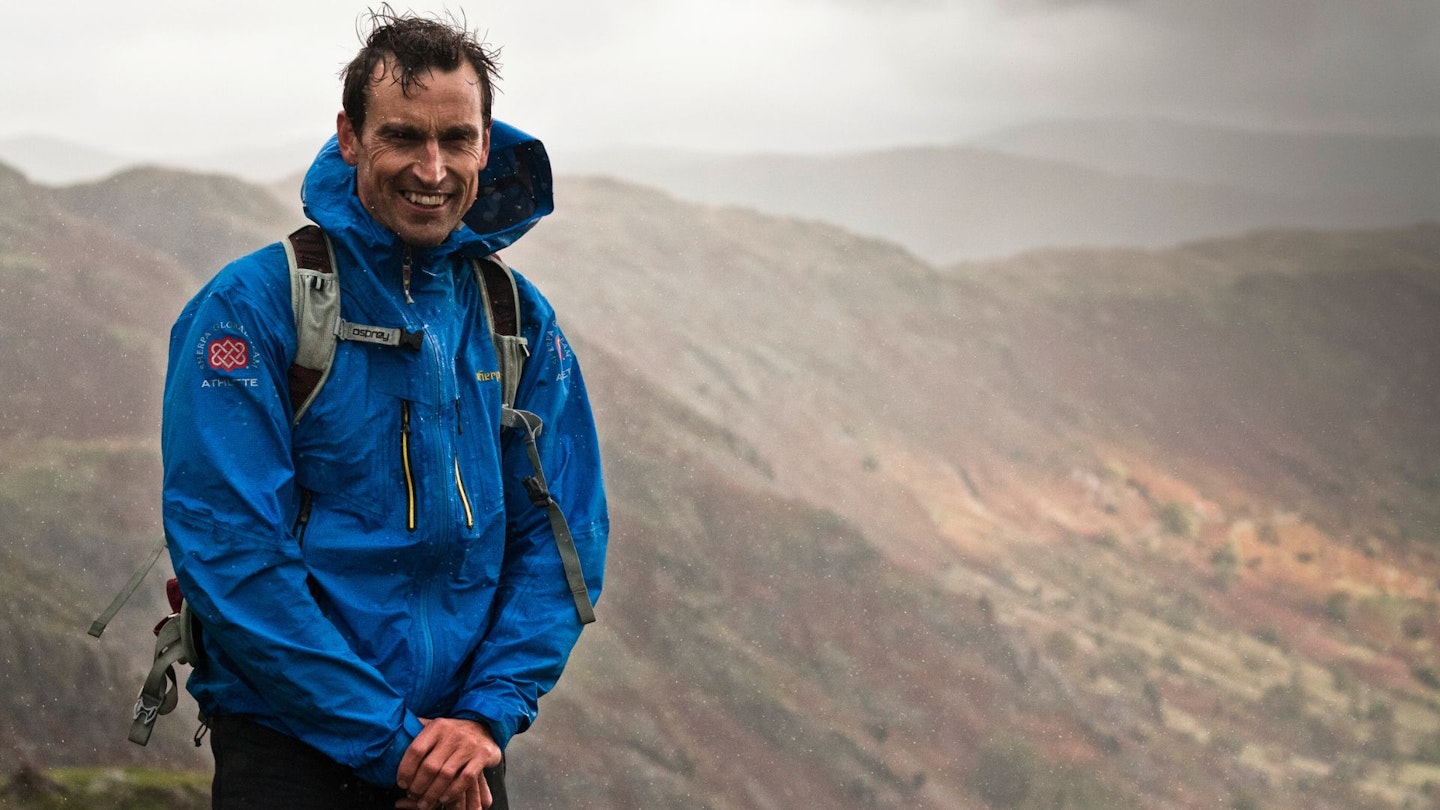

Kenton Cool first summited Everest in 2004. Then he did it again in 2005 after being clocked on the head by a falling rock and requiring stitches. In the 20 years since that first climb he’s guided Sir Ranulph Fiennes to the top, skied down multiple 8,000m peaks and was the first British guide to lead a client to the summit of K2.

Last year, he summited Everest again, for the 18th time – the most of any non-Nepalese person – and at the time of publishing, he's back on the mountain and attempting summit number 19.

We caught up with him to find out a bit more about what the world’s highest mountains have had to teach him.

1. Look after yourself so you can look after the team

On my first Everest expedition, in 2004, I spent 16 days at Camp Two (6,400m) or higher, and came down carrying a massive rucksack, empty oxygen cylinders and all sorts. A climber who was mentoring me at the time took me aside and said, “What you’re doing is going to be respected and understood. But you don’t need to do it.”

That first year, I understood that leadership doesn’t mean you’ve got to do stuff harder, faster or better than anybody else. It’s a common misconception that leadership is all about being out there, being the first. But you’ve got to look after yourself.

2. Communication and collaboration are critical

You’ve got to earn the trust and respect of the people around you. This year (2022) everything went to plan, we had fantastic weather, an amazing team, and it’s easy to lead in that environment. It’s in times of crisis that you understand what true leadership is.

If you haven’t formed bonds with those around you, certainly on Everest, it can go badly wrong, pretty damn quickly. It’s super important to earn trust and respect, so that people follow you when you need it.

That comes down to spending time with your team. To laugh with them, cry with them, to be there when they need you. Then they know that they can lean on you without having to ask. Get the team on board and pretty much everything else falls in place.

3. The team is everything

I think the image of the leader being unapproachable or bulletproof is a very old way of looking at leadership. It’s 100% collaboration, communication and culture. People have got to be able to come up to you and ask questions.

They need to know that you are on their side and you’re there to pull for them, to be there for them as and when they need you. Nobody’s gonna summit that mountain on their own – or very few people.

For most of us, the outdoors is something that we love. It empowers us, it resets our mindset. It puts us in a good place. We challenge ourselves in the outdoors, whether it’s Sca Fell, Pen y Fan or Everest. But we are mere mortals and we need the support of the people around us.

4. As a guide, you're not there for yourself

When I was a younger guide in the Alps, I was so impatient. It was all about how fast I could go through the Icefall, how quickly we could go from Camp Three to Camp Four, or whether I could do that without oxygen.

But after about two or three years, the penny dropped that I’m not there for me – I’m there for the Sherpa team and the client.

5. It’s all about moderation

I still carry more than my fair share but I don’t carry the humongous loads that I used to. I don’t come slithering down the Icefall without my crampons on like I used to. Now that I’m older it takes longer to recover, so my whole approach to Everest has become one of moderation.

It’s hard work no matter how you look at it, but we try to build the expedition in a way that safeguards the client and the Sherpa team mentally and physically.

"Everest doesn't care who you are or how many summits you have. You've got to approach that mountain with your ego in check".

Kenton Cool

6. Manage your mental state

There are days when you’ve got your Gore-Tex on, it’s snowing and windy, you’ve been battered by the weather and you’re like, "What am I doing?". Sometimes it’s a crap day.

I learned from an early age from my father that if you walk in a room with a long face, you can affect everybody; if you walk into a room with a happy face, that’s even more infectious. It’s down to mindset.

When I’m in a foul mood, I’ll take myself off, have a word with myself, perhaps have a masala tea and bring myself back when I’m fit and ready to engage. We do these things because it’s meant to be fun.

If I wake up in a grumpy mood then my clients are generally going to have a really shit day and they’re only ever gonna go to Everest one time.

7. Know when persevering is helpful or dangerous

Sometimes you get yourself in a situation – chasing a storm or trying to get down before you get benighted – when you have to push things further than you normally would.

But generally, if you plan something properly, you have a very good understanding about how far you can push it before you, your partner or client collapses, mentally or physically. It’s a guide’s duty to push the envelope so that the client has a super fulfilling trip.

But you don’t want to completely blow the envelope apart and come back having had a miserable, horrible time. You potentially put them off mountains for life.

8. Trust your intuition

We all push things too far. Where you think, "We could just do this extra peak before the wind picks up." But when you realise you made a mistake, the interesting thing is, deep down, you often know you’re pushing the limits of what’s acceptable.

And when it goes wrong, you’re there going, “I knew it, I knew it”. It’s a gut feeling.

9. Leave your ego at home

Everest doesn’t care who you are or how many summits you have. You could have 30 like Kami Rita Sherpa, 18 like me, or none. You’ve got to approach that mountain with humility, with your ego in check, with no preconceived ideas about how fast, slow or successful you’re going to be.

I honestly think Everest respects that. We’ve all got ambition but rather than making wayward decisions, getting yourself or somebody else in trouble, it’s how you temper and channel that energy in a positive direction.

10. Respect the environment

Back in 2004, my first year, we got caught on the Lhotse Face. I went into it thinking, “This is nothing compared with a wild day in Scotland, these are a few snow flurries.” But on the Lhotse Face, when it snows, it comes hurtling down.

We got caught at the bottom trying to retreat across the fixed lines and the client completely disappeared in an avalanche. Then this hand came out, I grabbed the hand and pulled him out. Days like that, you should just hunker down in camp to give it a day to settle down.

You need to be respectful of the environment that you’re in and what you’re trying to do and know the consequences. We happily got away with it that year, but it could easily have gone in a different direction.

11. Allow for the uncontrollable

Understand that you’re in it for the long haul and plan for longevity, because you never know what’s going to happen. We were lucky in 2021, we sneaked up Everest on 11 May but then a series of cyclones hit and the next summit after the 12th was 23 May.

What happens if the unexpected or the uncontrollable comes in? It’s not a 100m sprint, it’s a 10,000m. You might bring it home in 5,000m, but plan on the 10,000.

12. Don’t wait for perfection

You can sit at base camp pontificating forever, waiting for the perfect forecast and chances are you’re going to miss the opportunity. The monsoon hits, there’s heavy wet snow forecast, winds pick up, the Icefall starts to melt and everybody goes home. So we don’t over-analyse it.

We’re not constantly waiting for our bodies to be 100%, for the best forecast or for logistics to be in place. More often than not, better is good enough. Certainly on a mountain like Everest where perfect days are few. Sometimes you just gotta go, “You know what? That’s good enough.”

13. Don’t worry about what others think

Ultimately, nobody really cares. One of the biggest inhibitors I think we have as individuals is the fear of what other people think.

And in reality, it doesn’t matter what other people think. It’s what you think. Are you ready? Are you going to have fun? What can you learn from this experience? There’s nothing like experience in the bank to keep you pushing forward.

14. The learnings are on the approach, not the summits

Whenever I get down from the mountain, I give myself a few hours to reflect on what worked, what didn’t work, what can be better, what we did right and, more importantly, what we did wrong.

Summit day is normally relatively seamless, because it has to be. And when things go seamlessly, what are the learnings? It’s when it goes south, it’s like, “Ok, what went wrong? Why? How do we avoid it?” Once we get to the top, what do we actually learn?

It’s the pitfalls along the way that we gain the experience from.

15. In times of crisis, defer to logic

I generally view summit day as one big exercise in crisis management, and in crisis management emotional decision-making doesn’t have a place. I try to base my decision-making processes on hard, logical facts, like the current state of the team, overhead conditions and time.

As soon as emotion slips in, your decision-making becomes clouded, based on conjecture. And that’s where things can start going wrong. It’s taken me a long time to get to that stage, but I think it’s super important. In times of crisis, decision making has to be clean cut and fast.

16. Patience is key

One of the most important traits in mountaineering is patience. The ability to sit in a tent through long periods of time and boredom and having tolerance for those around you.

You can be put in really stressful situations, in very close proximity to somebody else going through their own mental battles. If you overlay your own anxieties and stresses on somebody else, things are quickly gonna go south.

You can start falling out with climbing partners or friends. Having the ability to go with it and go with the suffering that comes with it, is an important thing.

For more on the highest mountain in the world, see our guide to Everest's most iconic features, or read about the man that's just swam, cycled, ran and climbed from the UK to the top of the world.