As we’ve previously suggested in our article on the best and worst outdoor films, there are a lot of stock moments we’ve come to expect in any film where walking/hiking plays a central role.

Hilarious mishaps. Eccentric characters. People getting ‘comically’ lost. Half-baked metaphors in which the hike symbolises someone’s internal turmoil. Romance, ridicule, redemption. And most of the time it’s done very, very badly – especially if you’re a viewer who really knows what walking is like.

But not this time. The Salt Path might be the most delicately beautiful – and real – film about walking you’ll ever see.

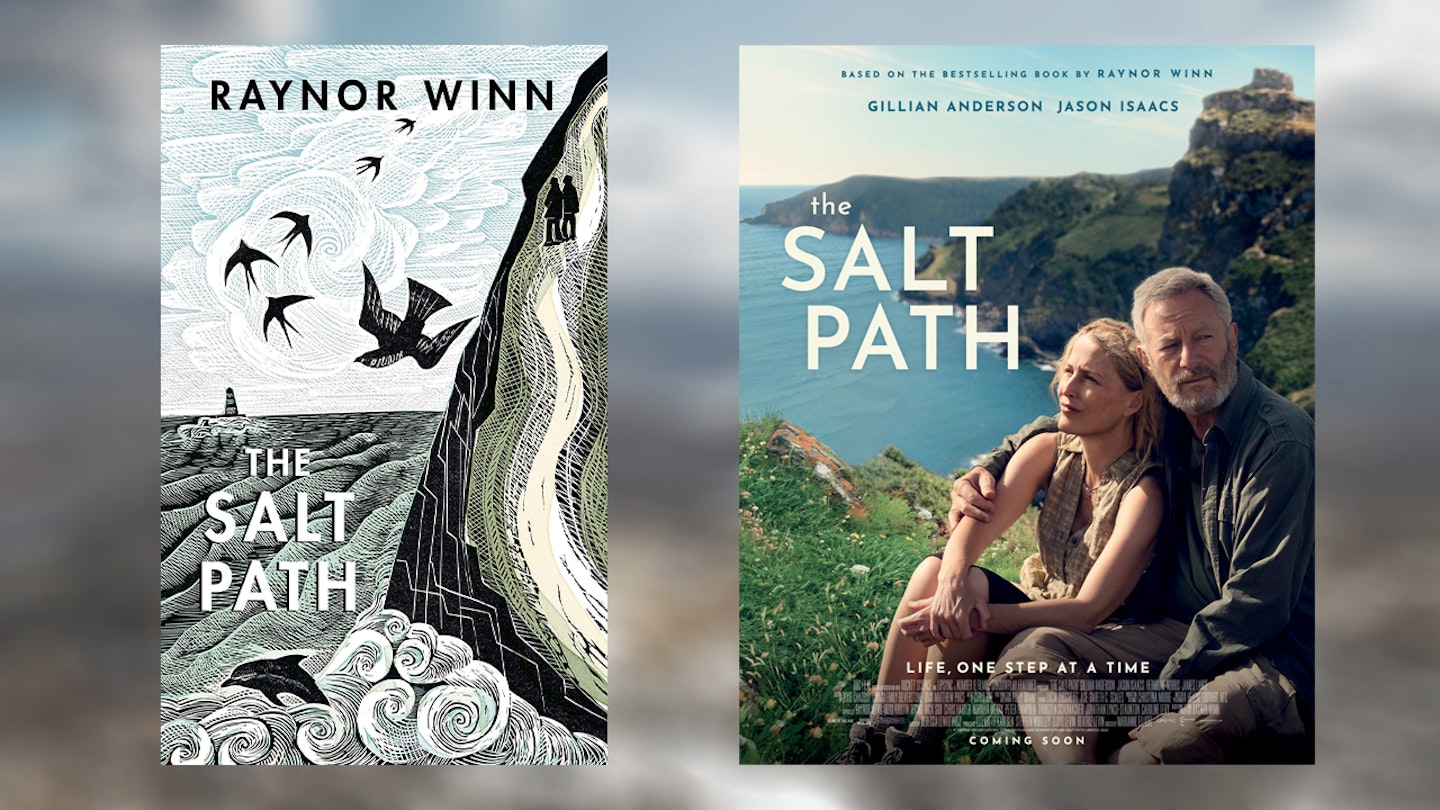

Two things help to achieve that. The first is that it has source material. Like 2014’s Wild, with which it shares some common DNA, The Salt Path is based on a book, which itself is an account of a real-life story. Also like Wild, that story is as raw as it gets.

The second is that, although more or less every scene takes place along the South West Coast Path, and involves boots, rucksacks, tents, views, snacks and blisters, this isn’t really a film about walking. It’s a film about people who go for a walk. There’s a difference.

The plot

UPDATE 7/7/25

At this point we should mention the fact that The Observer has this week published an investigation which casts doubt on the version of events presented in The Salt Path. For now, we’re choosing to keep the text of the review that follows as originally written, but you can find details of the Observer’s investigation, including a response from Raynor Winn, here.

The Salt Path is the story of Raynor and Moth Winn. In 2013, their lives were upended when Moth was diagnosed with the rare brain disease corticobasal syndrome, and given just months to live.

At the same time, the couple lost a court case stemming from financial difficulties, resulting in the loss of the Welsh farmhouse home they shared with their children.

At the point of hiding under the stairs as the bailiffs hammered on the door, Raynor spied a copy of 500 Mile Walkies, Mark Wallington’s comical account of walking the South West Coast Path, and at that moment decided that the couple could ‘just walk’.

They cadged a lift to Minehead and set out on the path with just a tent, the merest provisions and just coins in their pocket, not knowing how far they might get.

The Salt Path – a book Raynor wrote as a birthday present for Moth two years later – captured the story of what happened. When published in 2018, it became a global bestseller.

Which brings us to 2025, when the film version – scripted by Rebecca Lenkiewicz and directed by Marianne Elliott – brings the story to the screen.

Following the book

The film’s first smart move is to be faithful to the source. If you love the book, you’ll recognise not just individual episodes but specific conversations, thought processes, encounters – even the structure.

It cold-opens with the same two moments juxtaposed: an instant of panic on a benighted beach, and the fear and anguish as Raynor and Moth crouch beneath the stairs. Then we’re in Minehead at the start of the trail, and then we’re walking, and the backstory is slowly revealed in flashbacks, much as it is in the book.

Panic and dread, anguish and fear. As you might expect (and like Wild before it) this is a film freighted with heavy emotion. Sadness is woven through it like the footpath through the Valley of Rocks.

But is it dismal, miserable, a relentless gut-punch of a film?

No. Somewhere under the surface tension, glimpsed in the glances between Raynor and Moth even in the depths of despair, there is always hope. There’s even joy. And, as rare as the pulling of a razor clam from deep in the sand, a laugh or two.

‘You should take me back to the shop and get a different one,’ says Moth, ruing his pain and slow progress.

‘I don’t want a different one,’ replies Ray.

The director makes it her own

There are some tweaks to the text. For example, the book Raynor spies under the stairs is Paddy Dillon’s Cicerone guidebook to the South West Coast Path rather than 500 Mile Walkies, but that’s an excusable switch – especially as the guidebook becomes a character, with Raynor doodling in its margins and the pair referring to it directly as ‘Paddy Dillon’ (often with cold loathing for the author’s occasional gift for understatement).

I won’t spoil anything much more here, except to note one remarkable little trick – which I confess I didn’t spot on first watch and to which I was only alerted when I chatted to Raynor and Marianne Elliott for this interview.

Most of the film’s first 25 minutes are spent in extreme close-up, on the faces of Raynor and Moth as they attempt to process their situation. It’s close, claustrophobic, intimate, quiet. Tired eyes, a cramped tent, a glance downwards at slow footsteps.

It’s only when Ray reaches a particular hilltop, and for the first time begins to look outside of their trauma, that the camera pans back to show to show the immenseness and beauty of what’s around them. Raynor looks upwards instead of inwards, and so do we. Suddenly the film changes, subtly but fully, and we understand we’re on a journey.

Deft performances

Crucial to that journey are the performances of Gillian Anderson as Ray and Jason Isaacs as Moth. Perhaps they may not look quite the way you imagined the couple when you read the book, but they embody the spirit and the will of Raynor and Moth with deftness and dignity.

Considering the dramatic range and glam factor of the two stars (The X-Files, Harry Potter, Sex Education, The Crown, Star Trek), they play this one stripped-back and raw.

Their authenticity may partly stem from the fact the actors spent some hours walking the trail with their real-life counterparts. It was Raynor and Moth who showed them how to put up the tent, badly at first and later like ninjas.

Gillian Anderson captures Ray’s intensity, her strength and her absolute sense of resolve. She has the same hardness as Raynor, and yet the same flashes of playfulness and quiet joy.

Jason Isaacs is the perfect foil: calm and witty in the face of adversity, yet just as determined to see this through. Even when he calls Ray ‘the Cake Police’.

The third character is the landscape, or perhaps more specifically, the sea. It’s a lovely touch at the start when the pair take a selfie, holding the phone at arm’s length ‘to get the three of us’. The sea is looked at wistfully at many points and yet you’re unlikely to get tired of it.

Other characters drift in and out, as they do on any real walk. In a lesser film, some of them – the haughty hikers in a rush, the irate landowner – would be played with a heavier hand (or worse, for laughs), but The Salt Path keeps it real.

Even the comedy of mistaken identity is deftly handled: Moth keeps getting mistaken for the poet and avid walker Simon Armitage, which actually happened – even though as far as we can tell, they look nothing like each other.

Does it hit the mark?

Some of it doesn’t quite reach the heights; the couple’s temporary adoption of the heartsick Sealy is an undercooked storyline, and some of the outbursts feel a little forced or stagey. I’d also wonder quite how well the film hangs together if you haven’t read the book.

And viewing it as a walker and a huge fan of the Coast Path, I would love to have seen a bit more exposition about what and where this path is. Apart from a fleeting glimpse of the map and a reference to its length (630 miles), there’s never much sense of where we are.

I can understand that the film-makers didn’t want it to be a travelogue, or to crash the drama with Indiana Jones-style progress maps, but I can’t help wondering if audiences in Chicago, Sydney or Shanghai would like to know a tiny bit more about where this is all happening.

You could also complain that the film doesn’t really build to anything. The ending just sort of happens. But director Marianne would tell you that was a deliberate choice. To build to some kind of crescendo or contrived catharsis would have seemed unfaithful to the book and to its lead characters.

Little moments, big messages

There are so many moments to treasure. The Beowulf performance. The salted blackberries. The sudden explosive rows and quiet moments of forgiveness. The nailing of those tricky Staffordshire accents by Anderson and Isaacs.

The film also has important things to say about the perception of homelessness. Watch the reactions when friendly conversations with affluent pubgoers suddenly judder to a halt whenever Moth – firmly, and with dignity – points out that they aren’t retired, they are homeless.

I also love the sound of this film. The sea is the near-permanent soundtrack of course, but so is birdsong, and wind, and the flapping of tent fabric.

But be warned: in its attempt to be faithful to the act of walking, it suffers from a saturation of respiration. I watched the film with someone who grumbled that ‘90% of this film is panting and grunting’. It’s a fair point.

But overall, the film of The Salt Path is a success. It’s raw and real; honest and authentic. It may well draw tears. It tells the story of two people who did something most of us might dismiss as sheer madness (or even irresponsibility), and yet within half an hour has us feeling like we understand exactly where Raynor’s understairs idea came from, and why it was the right response to what had befallen them.

It’s also a love letter to a landscape, and to the beautiful, brutal and bloody-minded act of walking.

And finally it’s a reminder that sometimes, in the darkest of moments, going for a walk is how the light gets in.

The Salt Path goes on general release from Friday.

Who's writing?

Nick Hallissey is the head of content for Country Walking magazine and Trail magazine and has been contributing to Live for the Outdoors for over 15 years. He’s an avid film buff, especially when it comes to films about walking – basically Mark Kermode with added Gore-Tex. He’s also the author of our in-depth interview with Raynor Winn and Marianne Elliott about the making of The Salt Path, which you can find here.