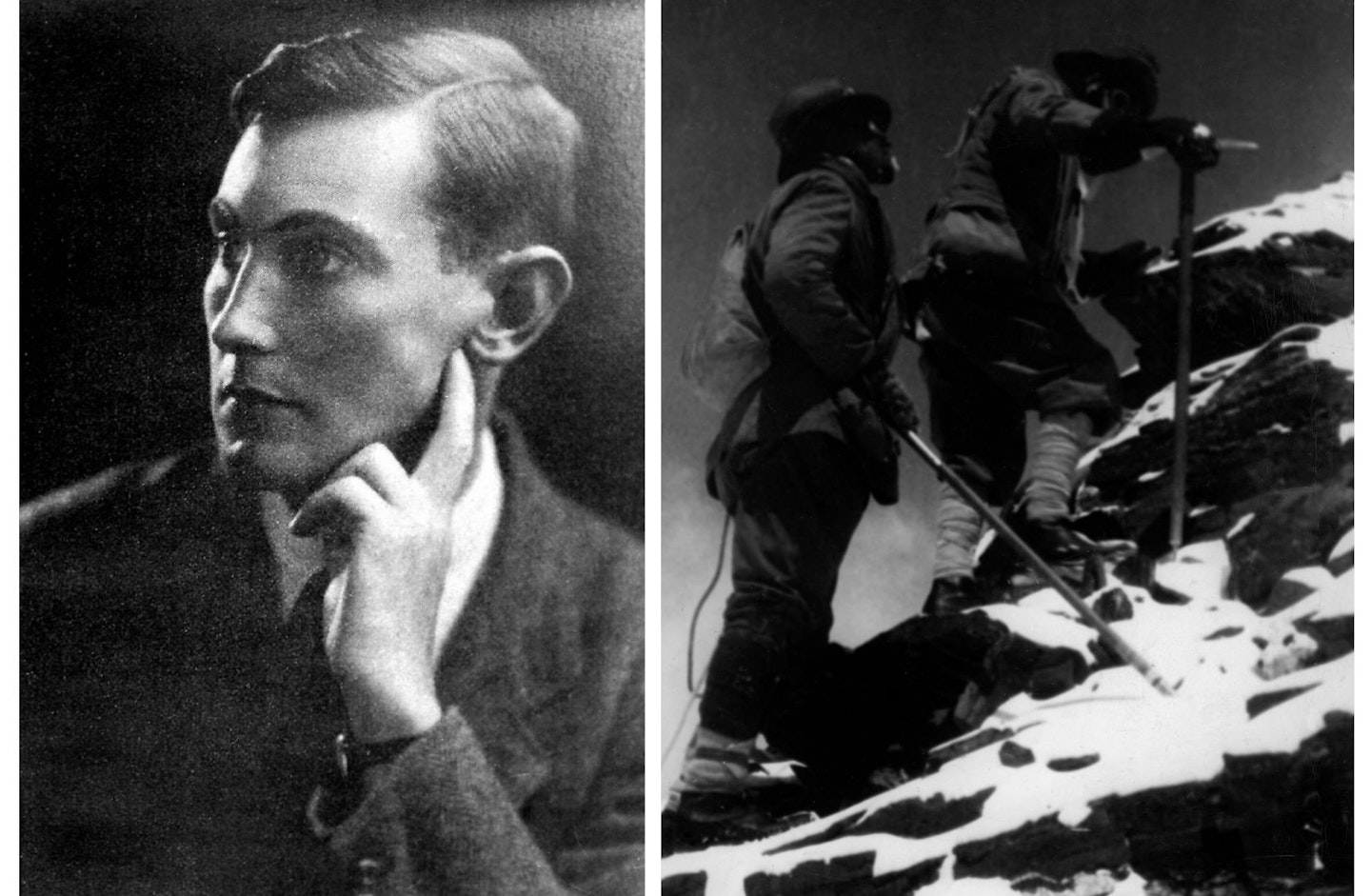

On 8 June 1924, Noel Odell, a climber and geologist on the third British Everest expedition, scrambled to the top of a small crag at 7,925m and peered upwards. The summit of the world's highest mountain had been enveloped in cloud for more than three hours, but at 12.50pm the sky suddenly cleared and he spotted what he was looking for: two black specks moving across the north-east ridge.

It could only have been his fellow expedition members George Mallory and Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine. Moments later, the clouds coalesced and a snow squall enveloped the mountain. The two climbers were never seen alive again.

One hundred years later, this image – of two men seemingly sublimated into the mist – has become part of the Mallory myth. He is remembered as one of the founding figures of mountaineering history, the only climber to partake in all three of the earliest British Everest expeditions, following the first in 1921 and a hasty return in 1922.

A tragic explorer hero who, like Scott in Antarctica, died in the pursuit of an ideal, an extreme geographic point, somewhere far from home. On a US lecture tour the year before, in answer to the question ‘why’, he famously answered, “Because it’s there.”

It’s probably the best known mountaineering quote of all time. A frank, sardonic quip with hints of compulsion and idealism. But still… why?

Mallory was a teacher with a wife and three children who, at the time of the third expedition, had just started a job that, after years of professional stagnation, he felt really hopeful about. Far from snatching the opportunity to return, the expedition committee had to go over his head to secure his leave.

For months before he swithered in indecision. Yet he went. And a century later many others still do. It wasn’t his only attempt to answer the question.

Throughout his life Mallory tried to understand and communicate the lure, describing “moments of supremely harmonious experience that remain always with us and part of us.”

Something of this is understood intuitively by anyone who loves the mountains – but what drew him to such an extreme? And what of that lives on today?

A desire for challenge

Mallory was born on 18 June 1886 in the village of Mobberley, about 15 miles south of Manchester. “He climbed everything that it was at all possible to climb,” remembered his younger sister Annie Victoria (Avie).

“I learnt very early that it was fatal to tell him that any tree was impossible for him to get up.” As a seven- year-old, he scaled drainpipes to the roof of his father’s church, climbed to the roof of the family home and continued as a teenager, scrambling over the buildings of his boarding school, Winchester College.

These roof climbing antics caught the eye of schoolmaster Graham Irving, a keen mountaineer, and resulted in Mallory’s first climbing trip to the Alps, in August 1904, aged 18. Mallory’s first experience of mountaineering was no gentle introduction.

He and Irving spent three weeks traversing glaciers, crossing high cols and attempting summits including Mont Blanc, which they ascended in a ferociously cold wind.

“It was certain,” Irving later recalled, “that he had found in snow mountains the perfect medium for the expression of his physical and spiritual being.” Mallory, apparently, came back elated, despite struggling severely with altitude sickness at the start, getting lost, and contending with the fatal dangers of rockfall and hidden crevasses.

He would return the very next summer. The hardship of the trip seems barely to have registered or, more likely, to have been an essential part of the appeal.

In later life, shortly before the third Everest expedition, Mallory would muse on the thing his sister recognised early: “Everest is the highest mountain in the world,” he said, “and no man has reached its summit.

"Its existence is a challenge. The answer is instinctive. A part, I suppose, of man’s desire to conquer the universe.”

The real feelings of sportsmen

As well as climbing, young Mallory excelled at football, shooting and gymnastics. Later, at university in Cambridge, he added rowing to the list, going on to captain the college rowing club.

In 1909, aged 23, he met Geoffrey Winthrop Young – a fellow roof-climber and, at 33, one of the leading Alpine mountaineers of the time. Young would become a lifelong climbing partner and confidante.

He first invited Mallory to one of his famous Pen-y-Pass climbing parties, held every Easter, and then to the Bernese Alps, where Mallory would demonstrate a striking boldness.

On one occasion, during an attempt on the as yet unclimbed south-east ridge of the Nesthorn, Mallory came up against a difficult and exposed overhang on a pinnacle near the summit. He was leading the group and had edged around the pinnacle on minute holds.

At the final overhang, he lunged upwards, failed to find a hold and fell 12m, caught by Young on a static rope which they later discovered was notorious for its low breaking strain.

Mallory climbed back up, seemingly unshaken, and at 7pm they reached the summit where they witnessed a sunset that he described to his mother as “the most wonderful I have ever seen.”

After this trip, a fellow climber would write of "his prodigious reach, his great strength, and his admirable technique joined to a sort of cat-like agility". Letters from this time sent by friends, acquaintances and would-be lovers rhapsodised about his physique, and George himself seemed to delight in his body and its abilities.

By 1912 he had made six trips to the Alps and numerous forays to the Lake District and north Wales. “Happily, as a sportsman myself, I know what the real feelings of sportsmen are,” he would later write.

The mountains represented a severe testing ground for his physical ability and mental focus, yet it was not only this that appealed. He was conscious too of some hard to define spiritual and aesthetic allure.

Commenting on its inherent dangers, he wrote, “The only defence for mountaineering puts it on a higher plane than mere physical sensation. It is asserted that the climber experiences higher emotions; he gets some good for his soul.”

A career path

The period between 1914 and 1920 saw Mallory’s personal life and the world at large go through a period of utter upheaval. The former, at least, was happy.

In early 1914, he met and fell in love with Ruth Turner. They were engaged in May, married in July and planned to honeymoon in the Alps in August, but it would be another five years before Mallory again visited these beloved mountains.

Six days after their wedding, Britain declared war on Germany. In January 1916, four months after the birth of their first child, Frances Clare, Mallory gained leave from his job to enlist and began the first of many long absences from home.

By privilege and good fortune, he came out of the war alive and physically unscathed, now with two more children, Beridge ‘Berry’ Ruth and John. He had been employed as a teacher at Charterhouse public school before the war, in a role which he found restrictive and uninspiring, and he continued to chafe when he returned.

Despite this, when he was approached about an Everest attempt in 1921, he hesitated. He had just returned from the war and his son John was only five months old.

It was his old climbing partner, Geoffrey Winthrop Young, who convinced him. Not by appealing to his aesthetic sensibilities or the prestige of the climb, but to the prospect of getting out of a boring job.

A symbol of adventure

The first Everest expedition, which took place largely during the monsoon, served ultimately as a reconnaissance mission, with no serious attempts on the summit but a route via the North Col identified.

The second came soon after, departing just three months after the first had returned. Again, Mallory was reluctant. “I wouldn’t go again next year, as the saying is, for all the gold in Arabia,” he wrote in a letter to Avie.

He saw too many difficulties, too many dangers, such little chance of success. In his expedition report he stated that “It is not to be a mad enterprise rashly pushed on regardless of danger.”

Yet the notion of watching other men succeed on the route that he had established, or of leaving a challenge unmet, a job undone, seems to have been too much for him. By the end of November, two weeks after getting home, he was signed up.

Back on the hill, the spirit of the thing seemed to get back into him. “It became a symbol of adventure,” he wrote. “I imagined, not so much doing anything of my own will, but rather being led by stupendous circumstances into strange and wonderful situations.”

Editor's note: Find out the obstacles standing in climbers' way as they attempt to summit Everest.

The compulsion to climb

The reality was much more harsh. Mallory returned from the second expedition despondent, unconfident and bowed by consequence. During the third summit attempt, which he led, an avalanche triggered by the party swept seven Nepali porters to their deaths, bringing the expedition to an abrupt halt.

The avalanche was not the result of foolhardiness but of a lack of knowledge about the snowpack. Still, he and the rest of the team were appalled by the accident. In addition, bitter cold, thunderous wind, snow showers, and the fatigue and dehydration of high altitude had worn the dream down to a chore.

“Whether the summit of Mount Everest, had we attained it, would have aroused in us a quality of emotion worthy of the occasion is impossible to tell,” Mallory reported, “But we experienced certainly nothing of the kind at this highest point we reached. The stupefied brain had remained only capable of turning aside from all else and concentrating on the one grim task of pushing upward.”

He returned home without a job, and without the hoped-for new career, earning a small amount from lecturing fees and magazine articles. For a man with three young children, this was hardly reliable and in 1923 he secured a job teaching history to working people around Cambridge – a role that he was finally really excited about.

When the query about the forthcoming 1924 expedition finally arrived, Mallory, again, oscillated. Len Winthrop Young, first president of the Pinnacle Club, recalls him confessing that “he did not want to return to Everest.”

Yet, in his own words to an old friend, he felt a compulsion. With just two weeks to go before the sailing, he signed the contract.

A way of salvation

The first Everest expeditions took place in the earliest shell-shocked days following a war that killed an estimated 22 million people; born of a country with a calcified class system, particular ideals around masculinity, and imperial notions of conquest.

But the people who climbed it had their own personal reasons for doing so: physical challenge, career opportunity, beauty, scientific endeavour, commitment, loyalty, stubbornness, a sense of spiritual and physical ascension.

In his article The Mountaineer as Artist Mallory tried to put the lure and emotional experience of mountaineering into words: “We set climbing on a pedestal above the common recreations of man,” he wrote.

“We set it apart and label it as something that has a special value.” While climbing "a divine completeness of harmony possesses all the senses and the mind as though the universe and the individual were in exact accord, pursuing a common aim with the efficiency of mechanical perfection."

It was, he declared, “one of the modern ways of salvation". It is tempting and easy to see his death on the mountain in that romantic light – a Grecian figure ascending to the heavens – but it must have been scary, it must have been cold, he surely wished to be home.

He wasn’t, after all, a myth. He was a man with a family and a twice broken leg high on a mountain he had never quite managed to escape.

For more Everest content, here are 16 lessons that 19 summits have taught mountain guide Kenton Cool.