Officially, nobody's died. Or been horribly injured. Officially. Check back through the online archives of the Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Team and you'll not find one mention of anybody meeting their end while attempting the jump between Tryfan's iconic Adam and Eve stones.

The records go back to 1961 and among the dozen or so incidents logged for Tryfan's summit are sprains, dislocations, fractures, and sadly one fatality. But only one of them – a dislocated shoulder in May 2001 – has been directly attributed to the casualty having come a cropper leaping between the biblically monikered monoliths.

Which, if you've spent any time in the company of Adam and Eve, is both encouraging and really rather remarkable.

If you're unfamiliar with Adam and Eve (and I don't mean the snake-charming naturist couple), then clearly you’ve never climbed Tryfan. The two towering boulders mark the 917m top of Wales' most desirable peak and, standing as they do at around 8 feet tall, there's no chance you'd miss them if you've been to the summit.

Having said that, you don't actually have to climb the mountain to see Adam and Eve. Their stature is such that. when the summit's not shrouded in cloud, their outline is visible from the base of the Ogwen Valley. Of course, from there you can't jump between them.

Mountain lore has it that completing the jump from one of these plinths to the other gives you the freedom of Tryfan, although mountain lore is a little fuzzy on exactly what privileges this bestows. It's more about kudos and bragging rights.

But unless you've been there, standing on top of Adam, considering your next move, you might have difficulty getting your head around what the big deal is.

Tryfan is acknowledged as being one of the few UK mountains that require hands as well as feet to reach the summit. Getting to the top demands a head for heights and scrambling abilities. By the time you reach the top you know you've climbed a mountain; then there, between stone and sky, you're greeted by the twin sentries– Adam on the left. Eve on the right.

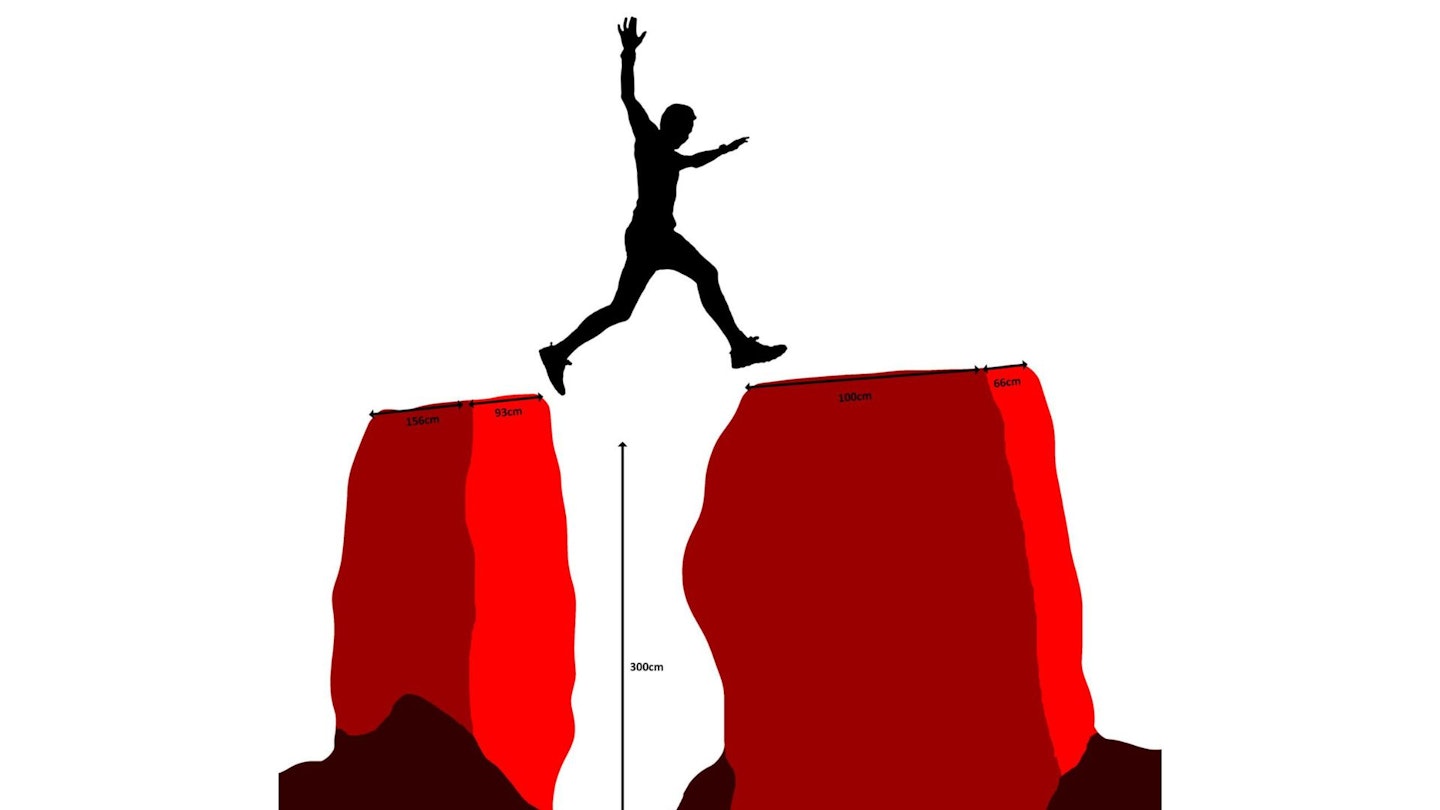

The next step is to climb aboard one of them. At around two-and-a-half metres tall, this is no mean feat. Footholds are virtually non-existent, and the few that do exist are thin and rounded. Hauling yourself onto either rock is as much about will and determination as it is about technique. It isn't a graceful manoeuvre.

As you rise to your feet, wind testing your balance, you gain an appreciation for the precariousness of your position. The platform on which you stand measures roughly 4 feet across. Sounds roomy, doesn't it? It's not when you're up here.

The rock beneath your boots is skewed, sloping and worn smooth by the thousands of soles that have passed this way. Eve is the chunkier of the two; Adam is narrower and tapered. Whichever you're standing on, the other looks no more inviting, and that four-foot gap that seemed a mere skip from the ground is now a more significant obstacle.

Then there's the height. Your presumably unhelmeted skull and the soft but valuable organ it contains are now approximately 15 feet above the rocks covering the summit. But you're not looking at the ground on which your pedestal stands; you're looking at the ground below that.

To the east, the mountain comes to an abrupt halt mere inches from the standing stones, then plunges 200m down the rock-strewn slopes of the Heather Terrace. To fall in that direction would be fatal. And still the wind teases..

A small group has gathered below. It's either jump or admit defeat. You'd rather not back down. This is something you want to do, dammit. Concentrate.

You shuffle to the edge of the stone and ready yourself. The other platform is little more than a step away, but it still niggles. The soles of your boots grind into the rock to find grip, you rock back slightly, take a breath, and launch.

The amount of time you're in the air, arms outstretched, feet free of any earthly contact, is a fraction of a fraction of a second. But in that fleeting moment, it's not the hard stone of Tryfan's summit or the steep drop to the side that holds your attention.

Your whole being is focused on one thing: the other pillar. Will you be able to stop? Is the stone damp and slippery? Have the countless leaping boots left the boulder glazed and frictionless? Will your own fail to find any purchase, sliding over the edge and dumping you, bruised and broken, on the rocks below?

Your outstretched foot lands and your toes curl within your boot, attempting to cling to whatever grip there is. Your trailing leg follows and both feet push hard at the surface, knees bent, body weight forced down to fight your momentum. You straighten up and breathe out. It's okay. Everything is okay. You made it.

Of course, if you jumped from Eve to Adam, technically you need to turn around and make the return journey.

Despite the esteem in which this manoeuvre is held, whether you choose to take it on is entirely up to you. Anyone who's made the jump should have as much respect for somebody who has sized it up and decided not to take the risk as they have for the thousands of fellow jumpers with whom they're obliged to share the freedom of Tryfan.

Because once you take away that basically hollow reward, what's the point? Perhaps that's why there are so few official records of Adam-and-Eve-related injuries. Nobody wants to admit to requiring the assistance of Mountain Rescue as the result of what is essentially an unnecessary stunt.

But people will continue to take the challenge nonetheless. Why? Well, why do we climb mountains at all? The reasons are the same: because we want to. Because it pushes us, it excites us, and it's a cool thing to tell your mates you've done.