Here at Live for the Outdoors, we love maps. But we’ll admit one dark little secret: they can make idiots of anyone. Go on, admit it. Even if you’ve used and loved Ordnance Survey mapping for years or even decades, there’s been that one time (possibly more) when you got it a tiny bit wrong. Hopefully it didn’t have a big impact on your day. Or at least, no one noticed.

And sometimes it feels naughty to admit there are basic things about a map that you’re not quite sure about. “I can’t admit I don’t know that,” you might think. “I’ll look like an idiot.”

Would it come as any surprise that everyone in the Live for the Outdoors team (and our partners on Country Walking and Trail) gets that same feeling sometimes?

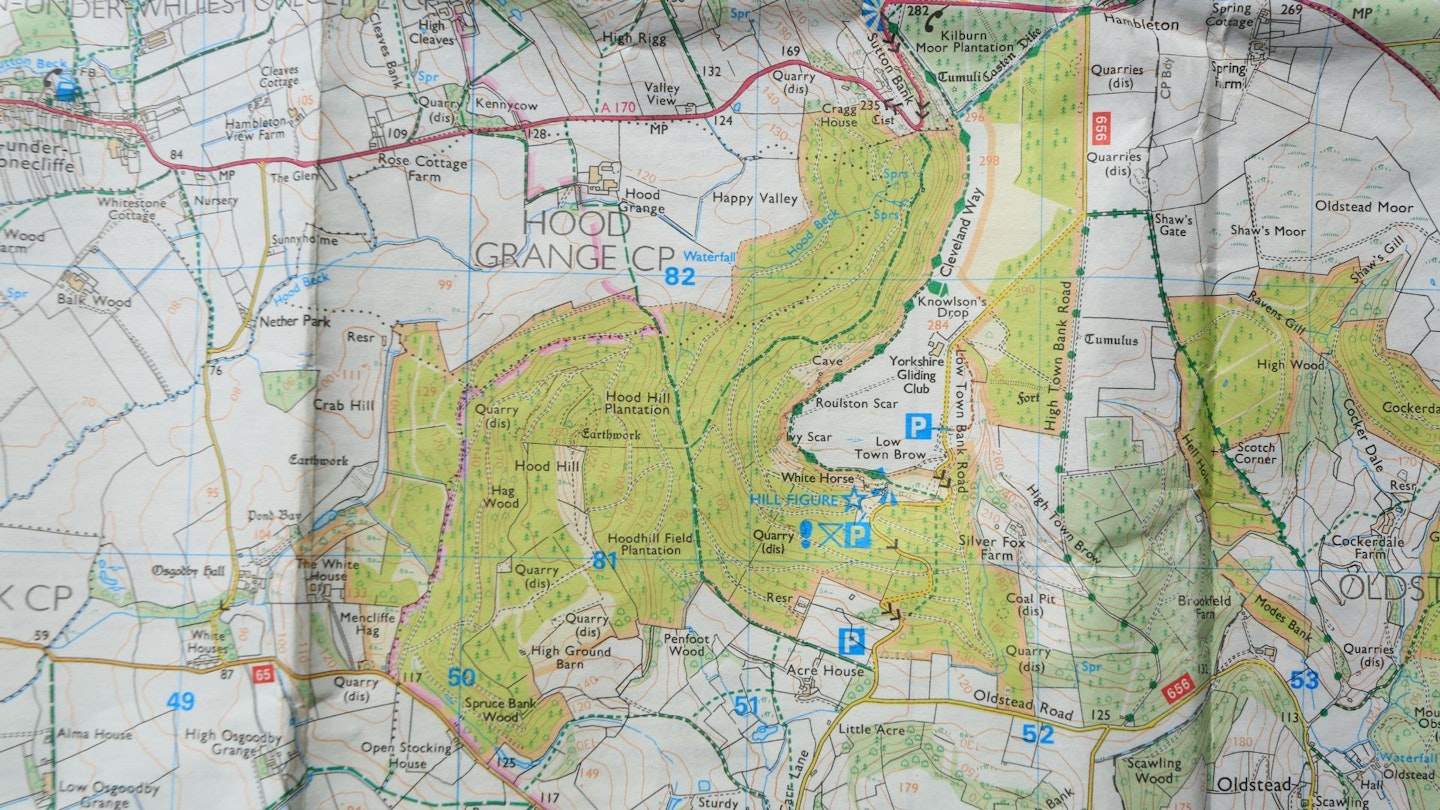

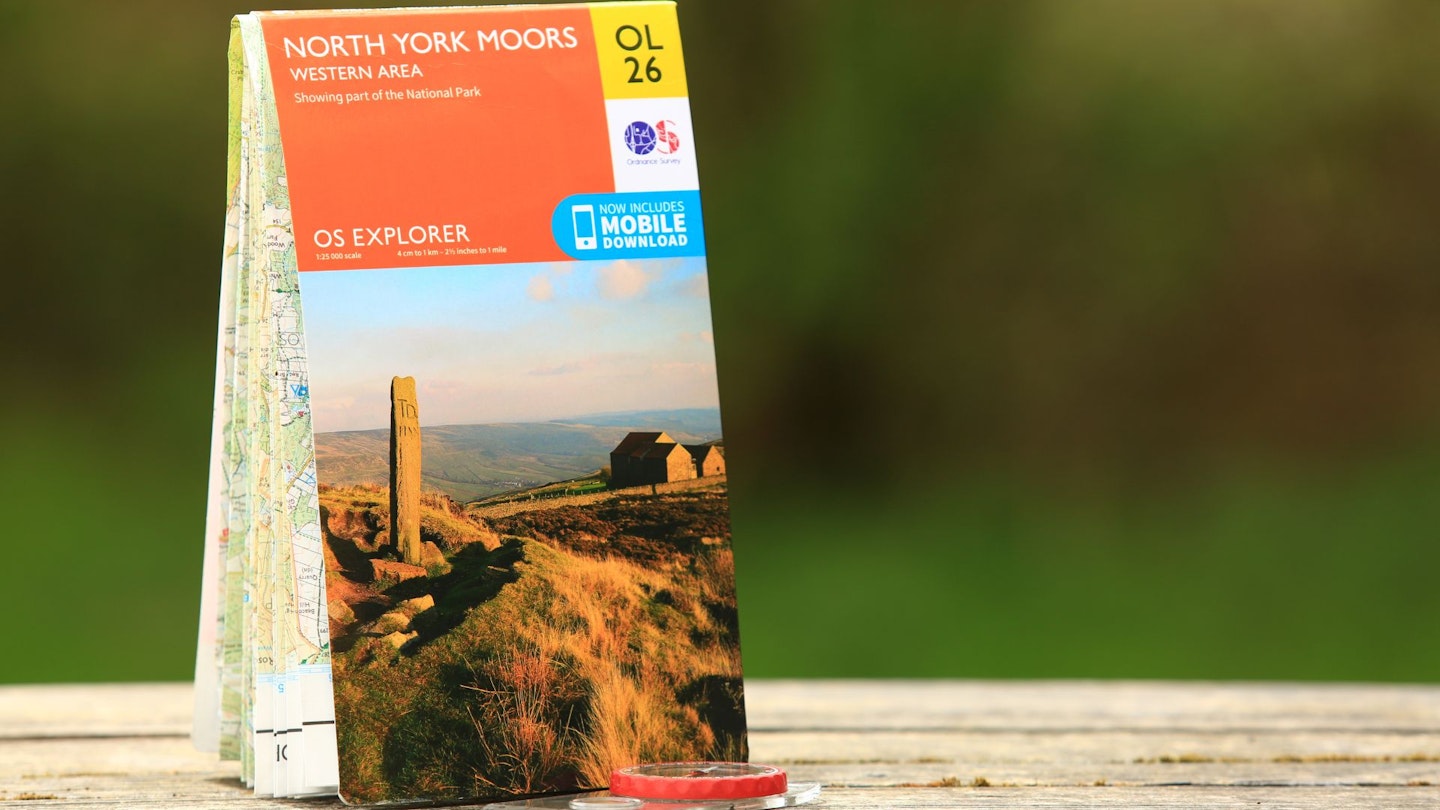

So we thought about this, and how we might help to fix those feelings. And this is what we came up with: a plan to find a patch of (beautiful) walking country that had every key feature that is useful to walkers on the OS 1:25,000 map (commonly called the Explorer range). And not just to show how it looks on the map, but what it (usually) looks like on the ground, too.

It was a tough search. You’d be surprised how hard it is to find a single patch of land that has all the features you’re about to see. But eventually we found our location: the forested cliffs south of Sutton Bank, at the western edge of the North York Moors – pictured below. (You can find it on OS Explorer Map OL26, or on the OS Maps app, of course.)

So read on, and whether you reckon you don’t know one end of a map from the other, or you’re a seasoned navigator silently longing for a bit of a refresher, hopefully there’s some intel here that removes the idiot factor for good.

NB: For the purposes of this feature we’re looking at mapping in England and Wales. Scotland has a general right of access which means there isn’t the need for as many types of lines and squiggles (especially not the green ones).

Part 1: Lines you can walk

Footpath

In amongst all the thick, coloured lines on this bit of the map, it could be hard to spot this faint black dashed line. But this is the symbol of a footpath. It means there is a footpath on the ground at this point. Whether you’re legally allowed to use it or not depends on the colour of the paper/screen around it.

In this case, the yellow wash denotes Access Land, which means you’re good to go. If it’s sitting on plain white (private land), it’s a no-go unless there’s a sign on the ground specifically saying you’re allowed access (eg. a dedicated nature trail on otherwise private land).

Of course, the presence of a footpath line does not guarantee the quality of said path. It might be a muddy mess, or barely discernible. In this case, though, it was fine. See?

Right of way #1: Footpath

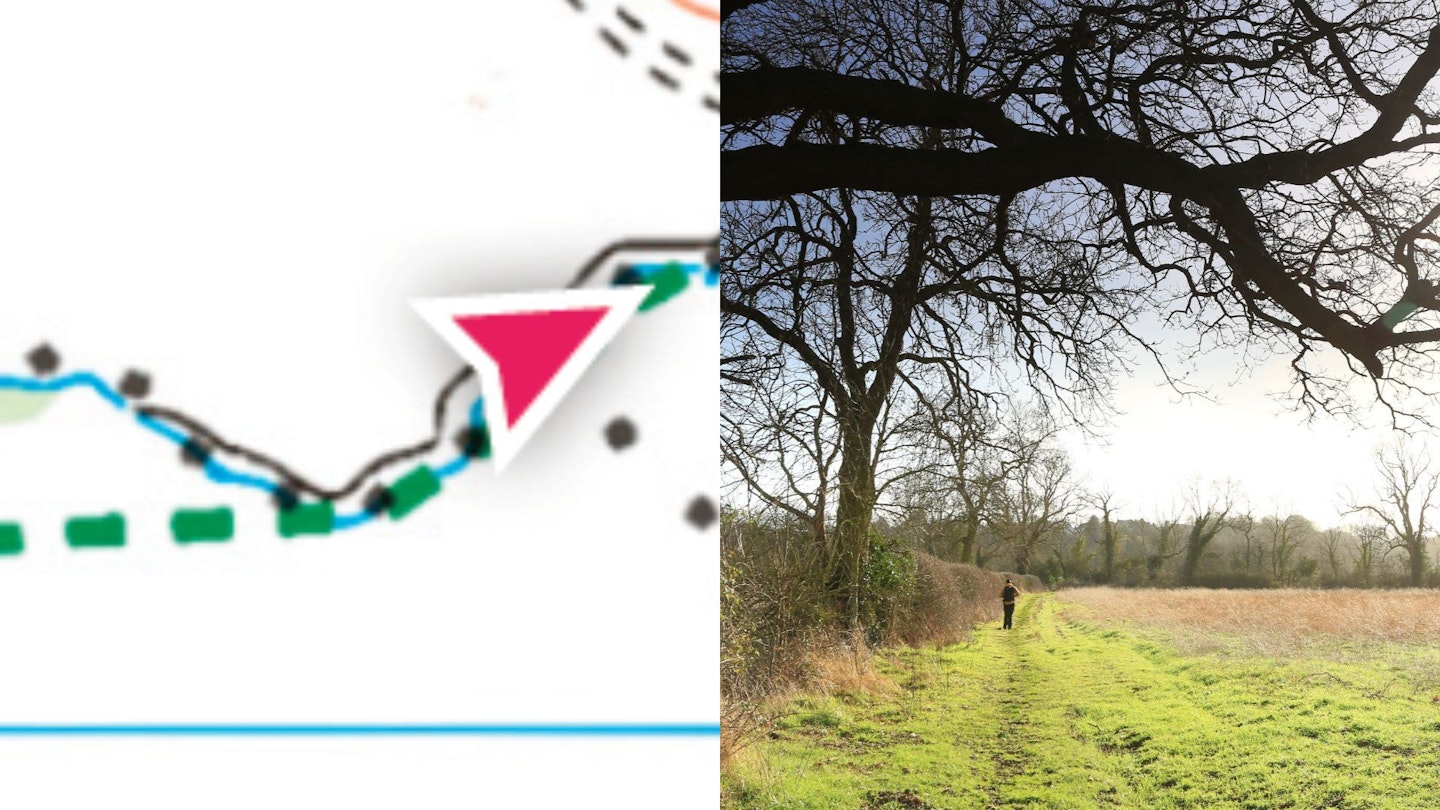

Any green line on the map is a right of way, which means whatever the colour of the land around it – Access Land or not – there is a legal right to walk that line. The short dashed green line is a pedestrian right of way (ie. foot traffic only).

The only thing that complicates this is that there might not be an actual footpath on the ground. But look closely at my arrow and you’ll see a black dashed line beneath the right of way. And for the walker, that combination is heaven.

It means you’re legally permitted to walk there (even though it’s outside the yellow wash so it’s not Access Land) and there is a physical footpath on the ground. To prove it, here’s me walking on it.

Right of way #2: Bridleway

This line of longer green dashes means there is pedestrian access but you can also legally ride a horse or a bicycle along it. Which generally means they’re broad and well-made, like this forest track. It also means you’re unlikely to encounter a stile.

Right of way #3: Long-distance path

The diamond-studded green line is the walker’s golden ticket. It denotes a recognised long-distance path, which means you’ve got legal access, usually a visible path on the ground, and probably some helpful waymarking and signposting – especially if it’s a National Trail, like the Cleveland Way in this case. It won’t always look as clear and manicured as this, of course. But it should at least be evident.

Check out how to walk a long-distance trail.

Right of way #4: Byway open to all traffic

Any human, animal or vehicle can use this line of green crosses – usually a track of some kind. But as it’s generally going to be a rough, unmade track, you’re unlikely to encounter a Vauxhall Corsa; more likely a Land Rover, quad bike or trial bike.

If it only had dashes on one side, it would be a restricted byway – no motor vehicles. (Similar to a bridleway; the only difference is its legal status.)

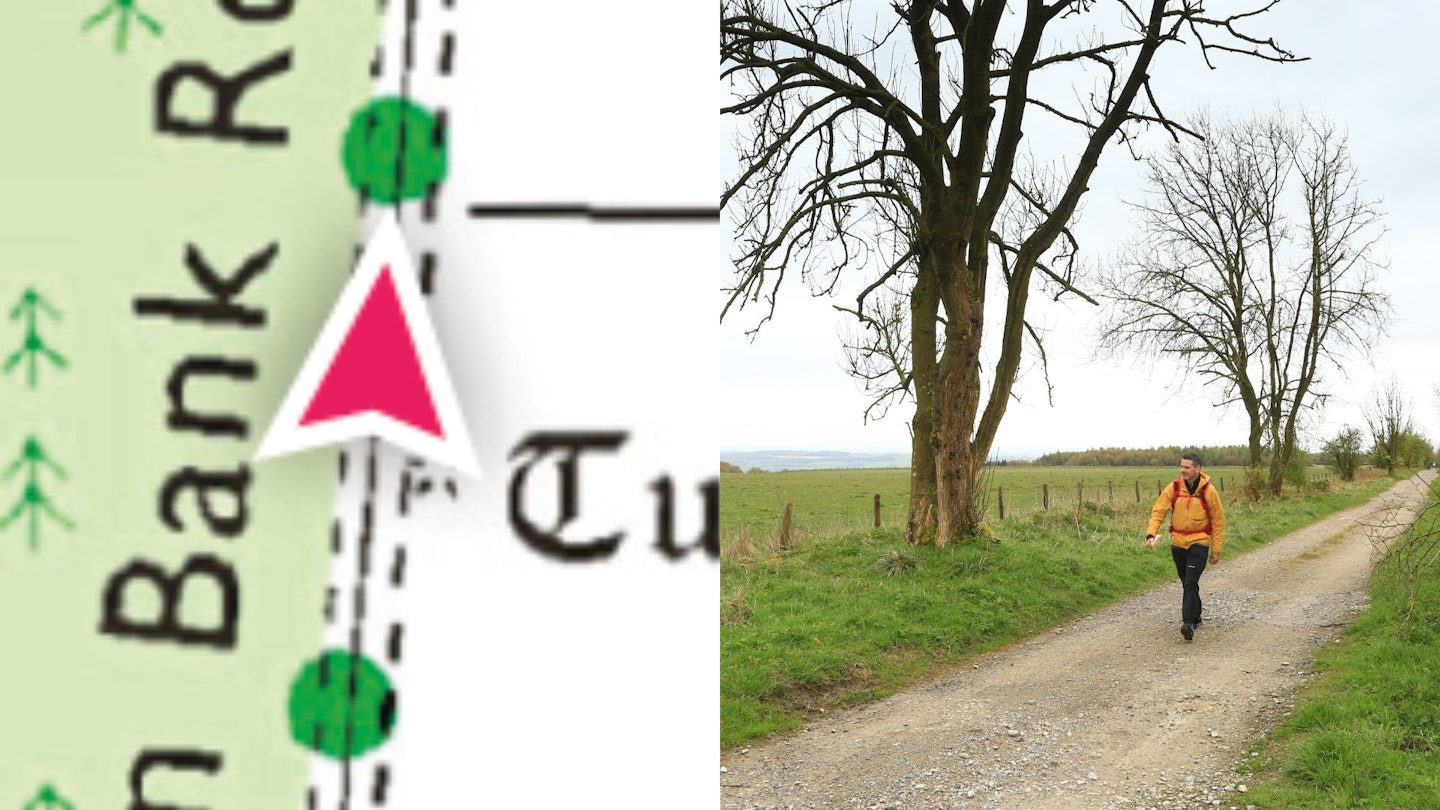

‘Other route with public access’

The green orbs are a funny one. There is public access, but the specifics may vary. They’re most commonly farm tracks. In general, you can use these unless there’s a big obvious sign on the ground saying you can’t.

Permissive path

The orange dashes are a permissive path: a viable route (seen here with footpath line beneath) that doesn’t have automatic right of way but is open to pedestrians by permission of the landowner. But they reserve the right to close it when they want to. There’s usually a sign saying so at the entry point.

Part 2: Access

Access Land

If the land on your map is covered in a yellow wash like this, it’s Access Land and you can walk across it at will – even if there’s no footpath, either on the map or on the ground. (Whether you’d want to or not is another question; it might be densely forested, unfeasibly steep or impenetrably boggy.)

In this case the yellow wash is obvious in the open clearing, but harder to spot when it’s sitting over a green wash of woodland. Landowners have a right to close Access Land for up to 28 days a year, but they must advise of closures in advance online and on the ground. If you’re on the coast, the equivalent of Access Land is known as Coastal Margin, and the wash is pink.

Private land

If it’s plain white on the map, it’s private. If I stepped left or right off the ‘other route with public access’ here, I’d be trespassing. So I didn’t.

Part 3: Natural features

Cliffs and crags

Look closely at my locator arrow on this map and you’ll see some faint grey squiggles next to me. Listed as ‘outcrop’ on the official OS map legend, you’re more likely to know them as cliffs or crags. Which means they’re either going to block your way or offer a stupendous view, depending on whether you’re above or below them. Here, obviously, I’m on top.

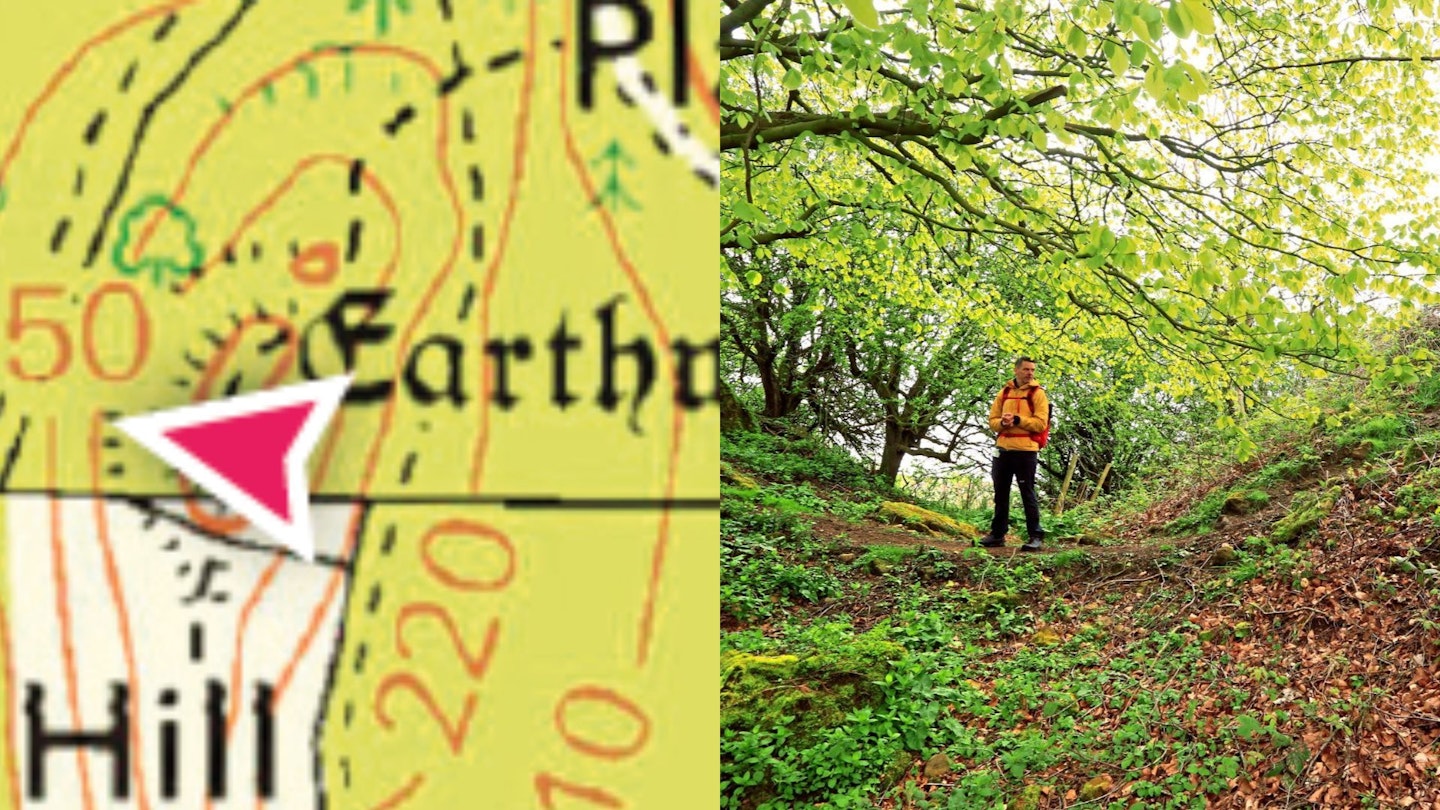

Earthwork

Usually written in archaic script on the map to denote ancientness. In this case, the earthworks are the circuit walls of an Iron Age hill-fort at the top of Hood Hill. Other archaic sites on the map include Roman forts and medieval halls or places of worship.

Part 4: Invisible things

Contour lines

I probably don’t need to tell you that contour lines aren’t visible on the ground. On the map, they simply denote the altitude of the land. The closer together the lines are, the steeper the ground is. Here I am, climbing some nice gradual ones on the summit ridge of Hood Hill.

Parish boundary

Here’s a tricksy one. Black dots, thicker than a footpath, nice and wiggly. Must be a path of some kind, right? Alas no, it’s a parish boundary. Invisible on the ground and offers no access or path at all. As you see in the photo, there’s nothing but private field to the right of my right of way.

National park boundary

If I headed a bit further north on this map, would I come to a massive pink wall? I would not. It just denotes the boundary of a national park; in this case, the North York Moors. Nothing to see here.

Part 5: When maps 'fib'

As much as we adore OS, it’s sometimes the case that the map doesn’t quite match what’s on the ground. On this trip we found a few paths on the ground that didn’t appear on the map. (Luckily we didn’t hit the opposite problem – paths on the map which aren’t there in the real world – but that happens a bit if you venture further east onto the moors, where some ancient rights of way on the map don’t appear on the ground). Anyway, here’s me, using a perfectly good footpath – on Access Land, and clearly well-used – that the OS hasn’t caught up with yet.

We asked OS about this; they said trees often make things tricky: “We can confirm that the areas highlighted were updated in 2024 for our 1:25,000 mapping. Areas like that are typically captured from aerial imagery, so we can load the data into larger-scale maps which we can then generalise from. As this area is under trees, it makes it more difficult to see paths and tracks such as these, which may explain why they aren’t shown.”

Part 6: The super safe way to do it

Of course, there is one sure way to go walking and be certain of a great walk that doesn’t fall foul of nonexistent paths, misidentified crags or ‘footpaths’ that are actually parish boundaries. That’s to grab a copy of Country Walking or Trail and use one of their routecards, written and checked by someone who went and walked it, and designed to be as easy to follow as possible. Just sayin’.

Check our our expert advice on what to do if you get lost.

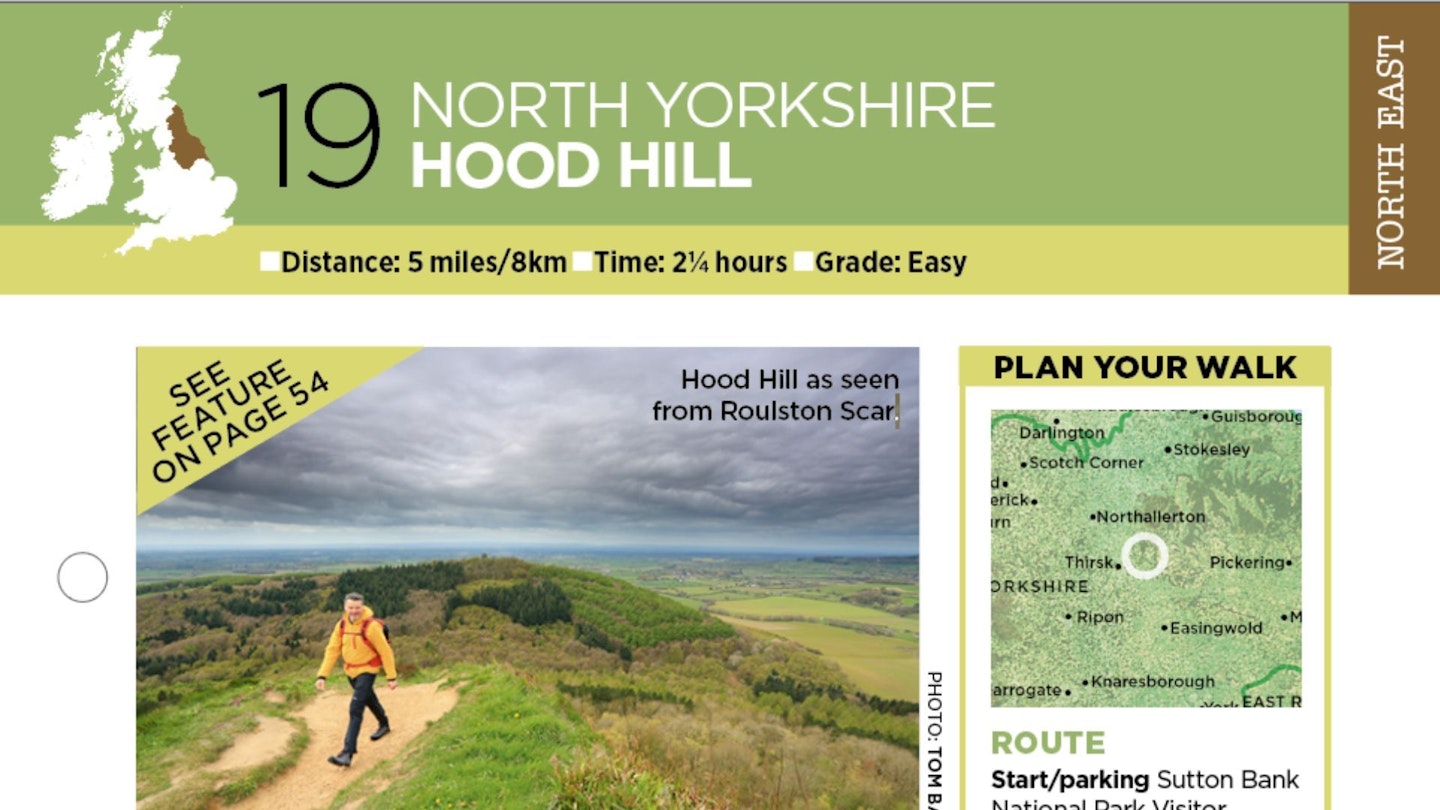

Now walk here!

Follow this link to our Hood Hill walk and you can spot all the footpaths, bridleways, rights of way and long-distance trails that are on here – and most importantly, enjoy a great walk too.

It’s just five miles long, meaning it’s also a perfect family walk, packed with gliders, huge views, a giant white horse, a mini-mountain (the highly unfrequented Hood Hill) and maybe even the chance to pass on your navigational nous to the next generation. There’s also a visitor centre at Sutton Bank for that well-earned ice cream at the end.

For more advice, read how to use a map and a compass.